Irish Rental Report Q3 2019 | Daft.ie

Daft Reports

- Ronan Lyons (House Price, Q1 2024)

- Ronan Lyons (Rental Price, Q4 2023)

- Ronan Lyons (House Price, Q4 2023)

- Ronan Lyons (Rental Price, Q3 2023)

- Ronan Lyons (House Price, Q3 2023)

- Ronan Lyons (Rental Price, Q2 2023)

- Ronan Lyons (House Price, Q2 2023)

- Ronan Lyons (Rental Price, Q1 2023)

- Ronan Lyons (House Price, Q1 2023)

- Ronan Lyons (Rental Price, Q4 2022)

- Ronan Lyons (House Price, Q4 2022)

- Ronan Lyons (Rental Price, Q3 2022)

- Ronan Lyons (House Price, Q3 2022)

- Ronan Lyons (Rental Price, Q2 2022)

- Ronan Lyons (House Price, Q2 2022)

- Ronan Lyons (Rental Price, Q1 2022)

- Ronan Lyons (House Price, Q1 2022)

- Ronan Lyons (Rental, Q4 2021)

- Ronan Lyons (House Price, Q4 2021)

- Ronan Lyons (Rental, Q3 2021)

- Ronan Lyons (House Price, Q3 2021)

- Ronan Lyons (Rental, Q2 2021)

- Ronan Lyons (House Price, Q2 2021)

- Ronan Lyons (Rental, Q1 2021)

- Ronan Lyons (House Price, Q1 2021)

- Ronan Lyons (Rental, Q4 2020)

- Ronan Lyons (House Price, Q4 2020)

- Ronan Lyons (Wealth, H2 2020)

- Ronan Lyons (Rental, Q3 2020)

- Ronan Lyons (House Price, Q3 2020)

- Ronan Lyons (Housing, July 2020)

- Ronan Lyons (Housing, June 2020)

- Ronan Lyons (Housing, May 2020)

- Ronan Lyons (Rental, Q1 2020)

- Ronan Lyons (House Price, Q1 2020)

- Ronan Lyons (Rental, Q4 2019)

- Ronan Lyons (House Price, Q4 2019)

- Ronan Lyons (Wealth, H2 2019)

- Ronan Lyons (Rental, Q3 2019)

- Ronan Lyons (House Price, Q3 2019)

- Pierre Yimbog (Rental, Q2 2019)

- Ronan Lyons (House Price, Q2 2019)

- Ronan Lyons (Wealth, H1 2019)

- Ronan Lyons (Rental, Q1 2019)

- Ronan Lyons (House Price, Q1 2019)

- Ronan Lyons (Rental, Q4 2018)

- Ronan Lyons (House Price, Q4 2018)

- Ronan Lyons (Wealth, H2 2018)

- Ronan Lyons (Rental, Q3 2018)

- Ronan Lyons (House Price, Q3 2018)

- Shane De Rís (Rental, Q2 2018)

- Ronan Lyons (House Price, Q2 2018)

- Ronan Lyons (Wealth, 2018)

- Ronan Lyons (Rental, Q1 2018)

- Ronan Lyons (House Price, Q1 2018)

- Ronan Lyons (Rental, Q4 2017)

- Ronan Lyons (House Price, Q4 2017)

- Ronan Lyons (Rental, Q3 2017)

- Ronan Lyons (House Price, Q3 2017)

- Katie Ascough (Rental, Q2 2017)

- Ronan Lyons (Wealth, 2017)

- Ronan Lyons (House Price, Q2 2017)

- Ronan Lyons (Rental, Q1 2017)

- Ronan Lyons (House Price, Q1 2017)

- Ronan Lyons (Rental, Q4 2016)

- Ronan Lyons (House Price, Q4 2016)

- Ronan Lyons (Rental, Q3 2016)

- Ronan Lyons (House Price, Q3 2016)

- Ronan Lyons (School Report, 2016)

- Conor Viscardi (Rental, Q2 2016)

- Ronan Lyons (Rail Report, 2016)

- Ronan Lyons (House Price, Q2 2016)

- Ronan Lyons (Rental, Q1 2016)

- Ronan Lyons (House Price, Q1 2016)

- Ronan Lyons (Rental, Q4 2015)

- Ronan Lyons (House Price, Q4 2015)

- Ronan Lyons (Rental, Q3 2015)

- Ronan Lyons (House Price, Q3 2015)

- Marcus O'Halloran (Rental, Q2 2015)

- Ronan Lyons (House Price, Q2 2015)

- Ronan Lyons (Rental, Q1 2015)

- Ronan Lyons (House Price, Q1 2015)

- Ronan Lyons (Rental, Q4 2014)

- Ronan Lyons (House Price, Q4 2014)

- Ronan Lyons (Rental, Q3 2014)

- Ronan Lyons (House Price, Q3 2014)

- Domhnall McGlacken-Byrne (Rental, Q2 2014)

- Ronan Lyons (House Price, Q2 2014)

- Ronan Lyons (Rental, Q1 2014)

- Ronan Lyons (House Price, Q1 2014)

- Ronan Lyons (Rental, Q4 2013)

- Ronan Lyons (House Price, Q4 2013)

- Ronan Lyons (Rental, Q3 2013)

- Ronan Lyons (House Price, Q3 2013)

- Ronan Lyons (Rental, Q2 2013)

- Ronan Lyons (House Price, Q2 2013)

- Ronan Lyons (Rental, Q1 2013)

- Ronan Lyons (House Price, Q1 2013)

- Ronan Lyons (Rental, Q4 2012)

- Ronan Lyons (House Price, Q4 2012)

- Lorcan Sirr (Rental, Q3 2012)

- Padraic Kenna (House Price, Q3 2012)

- John Logue (Rental, Q2 2012)

- Ronan Lyons (House Price, Q2 2012)

- Barry O'Leary (Rental, Q1 2012)

- Seamus Coffey (House Price, Q1 2012)

- Joan Burton (Rental, Q4 2011)

- Ronan Lyons (House Price, Q4 2011)

- Philip O'Sullivan (Rental, Q3 2011)

- Sheila O'Flanagan (House Price, Q3 2011)

- Rachel Breslin (Rental, Q2 2011)

- Constantin Gurdgiev (House Price, Q2 2011)

- Cormac Lucey (Rental, Q1 2011)

- Eoin Fahy (House Price, Q1 2011)

- Lorcan Roche Kelly (Rental, Q4 2010)

- Ronan Lyons (House Price, Q4 2010)

- John Fitzgerald (Rental, Q3 2010)

- Patrick Koucheravy (House Price, Q3 2010)

- Gary Redmond (Rental, Q2 2010)

- Jim Power (House Price, Q2 2010)

- Jill Kerby (Rental, Q1 2010)

- Brian Lucey (House Price, Q1 2010)

- Michael Taft (Rental, Q4 2009)

- Alan McQuaid (House Price, Q4 2009)

- Dr. Charles J. Larkin (Rental, Q3 2009)

- Emer O'Siochru (House Price, Q3 2009)

- Ronan Lyons (Rental, Q2 2009)

- Oliver Gilvarry (House Price, Q2 2009)

- Brian Devine (Rental, Q1 2009)

- Dr. Liam Delaney (House Price, Q1 2009)

- Gerard O'Neill (Rental, Q4 2008)

- Ronan Lyons (House Price, Q4 2008)

- Dr. Stephen Kinsella (Rental, Q3 2008)

- Moore McDowell (House Price, Q3 2008)

- Shane Kelly (Rental, Q2 2008)

- Fergal O'Brien (House Price, Q2 2008)

- Eoin O'Sullivan (Rental, Q1 2008)

- Dermot O'Leary (House Price, Q1 2008)

- Dan O'Brien (Rental, Q4 2007)

- Frances Ruane (House Price, Q4 2007)

- John McCartney (Rental, Q3 2007)

- Ronnie O'Toole (House Price, Q3 2007)

- Ronan Lyons (Rental, Q2 2007)

- Constantin Gurdgiev (House Price, Q2 2007)

- Fintan McNamara (Rental, Q1 2007)

- Rossa White (House Price, Q1 2007)

- Geoff Tucker (Rental, Q4 2006)

- Damien Kiberd (House Price, Q4 2006)

- Pat McArdle (House Price, Q3 2006)

- Marc Coleman (House Price, Q2 2006)

- David Duffy (House Price, Q1 2006)

- Austin Hughes (House Price, Q4 2005)

- David McWilliams (House Price, Q2 2005)

12th Nov 2019

The start of the end, ten years on?

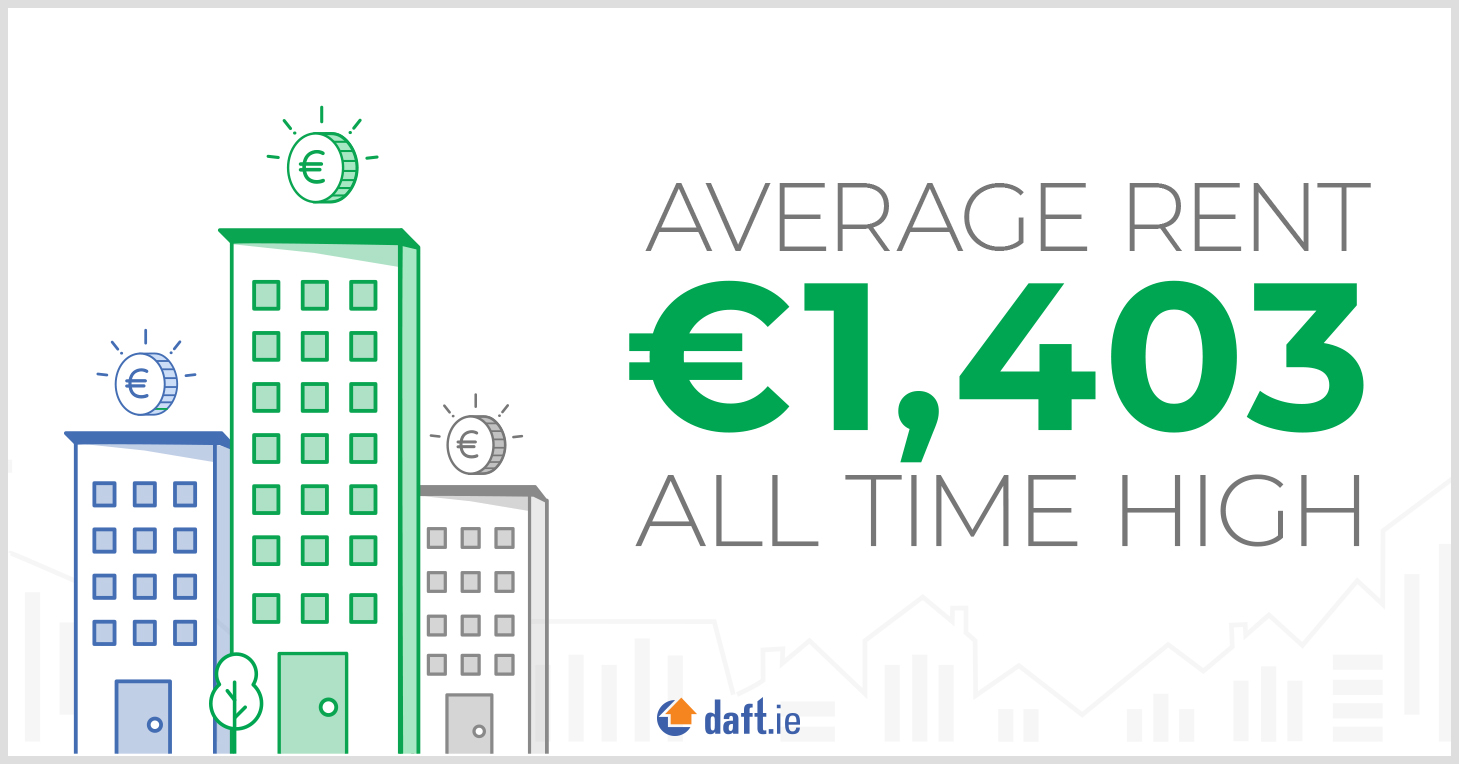

It looks as though Ireland's longest-ever run of increasing rental prices may soon come to an end. Nationally, inflation in the private rental market - as measured by the Daft.ie Report - has fallen from over 12% in mid-2018 to 5.2% in the third quarter of 2019.

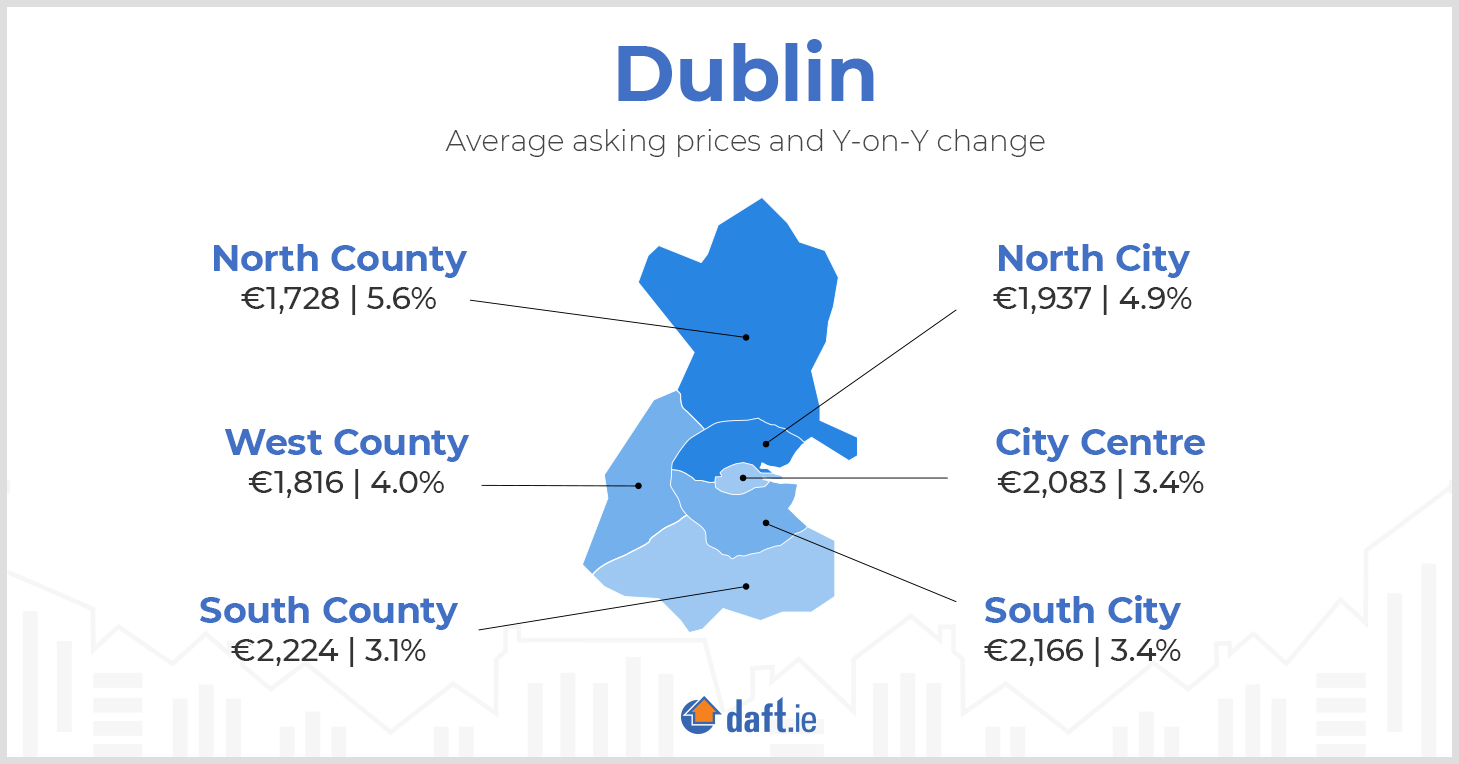

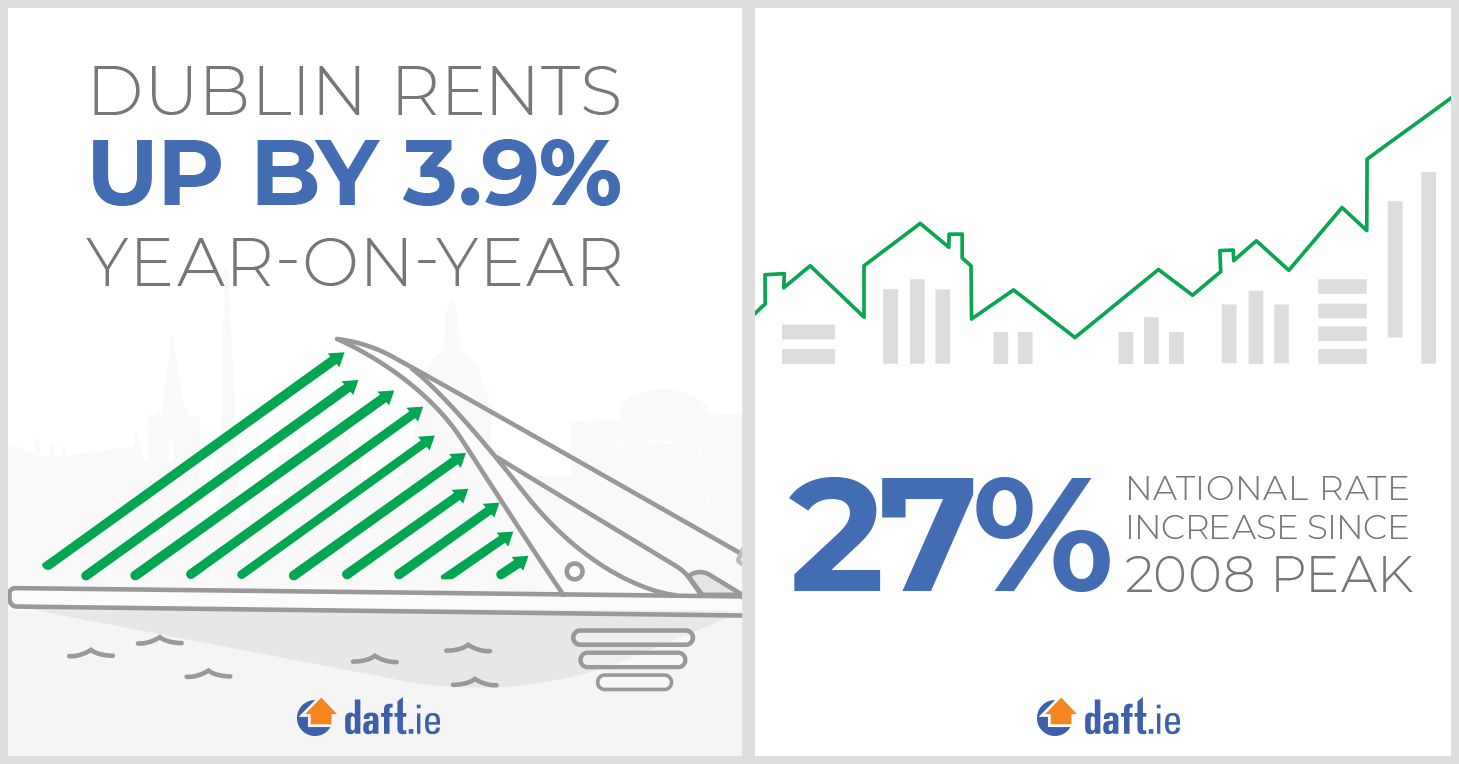

Dublin is driving this. Over the same period, inflation in the capital has fallen from 13.4% to just 3.9%. In four of the city's 25 markets - Dublin 1, Dublin 2, Dublin 4 and Dublin 20 - the inflation rate is now less than 2%. And in none of those 25 markets is inflation above 10%. This is the first time since early 2013 that this has been the case.

The fall-off in inflation may be driven by Dublin but is not limited to the city. As a general rule, other urban and commuter markets have also seen their rental inflation rates fall. For example, inflation in Meath has largely tracked that in Dublin, falling to just 3.6% in this report. And a year ago, rental inflation in Limerick city was over 20% - now it is 5.9%.

Taking a step back, this has been - by any metric - a remarkable phase of price growth in the Irish rental market. Rents in Dublin have more than doubled since bottoming out in late 2010. In Dublin 8, which has seen the biggest increase, rents have increased by just over 125%. The smallest increase was in South County Dublin, where rents increased by "just" 90% in 9 years.

In part of my academic research, I have been looking at the path of housing prices, both sale and rental, in Ireland over the last century. Much of this involves picking through what sources are available - including things like ads in the Irish Times and Evening Herald. As a result, we have a good idea of what happened to rents in Dublin for the last 75 years.

We can use the resulting figures to put this nine-year upswing in prices in perspective. Since World War 2, I can find only three phases where - stripping out general inflation - rents increased for more than four years. The first is the period 1959-1964, just after the crisis of the 1950s and as Ireland started to open up to international trade again. This upswing lasted five years. The second major upswing - between 1995 and 2001 - last six years.

The current upswing in rents has lasted almost nine years and counting in Dublin. Indeed, there are some pockets of Dublin where rents bottomed out in the second quarter of 2010. I highlighted the emerging shortage in my commentary on the rental report ten years ago. Analysing the figures for the 2009 Q3 report, I thought it was plausible that rents could level in Dublin - and perhaps the other cities - by mid-2010.

I don't bring this up to try and win awards for economic predictions. Predictions are - and always have been - a bit of a mug's game for economists. Rather, my point is that the trends that led me to that prediction - a growing lack of supply amid strong demand - was not difficult to spot.

One of the challenges raising the idea of shortages of rental housing in 2010 was that the system was so focused on the opposite problem: the problem of excess. But within about 18 months, the government had clear numbers on the number of unfinished estates around the country. This confirmed that there was no wall of available supply ready to come on to the market once conditions improved.

Instead, all the signs pointed to strong demand, including a natural increase in the population, a long-term downward trend in household size, and of course obsolescence of the existing stock. (Net migration did not add to housing demand until 2015.) Despite all these signs, it took years for the policy system to move from thinking about legacy problems of too many homes to current and future problems of too few.

Therefore, supply is key. And for new supply to come to the market, it must be viable to build. Commentators such as me have been arguing that construction costs and viability, especially of apartments (the typical rental home), are at the core of solving Ireland's housing crisis. It has been a tortuously slow journey for policymakers to agree.

Only in the last year has availability on the rental market improved from all-time lows. And only in the last year has rental inflation started to ease off. The two are not a coincidence. A remarkably stronger predictor of what will happen to rents over the coming three months than how many homes are on the market now.

The last rental report, published in August, highlighted that approximately 25,000 new purpose-built rental homes are on the way in Dublin and Cork over the coming five years. These are badly needed in both cities but only scratch the surface of true underlying need - which of course is not confined just to Dublin and Cork.

Policymakers should not settle for a system where rental supply can only be added to thanks to tax breaks (as in the early 2000s) or, as in the late 2010s, an extraordinary international macroeconomic environment that has led pension funds, with low yield targets, into residential real estate. Rather, they need to figure out why it is so expensive to build in this country and tackle that head on.

Otherwise, the market may not suffer another ten years of rising rents, but it will likely suffer another ten years of high rents. And for a country dependent on its attractiveness to workers and businesses that could easily set up somewhere else, that is not good news.