Irish Rental Report Q3 2020 | Daft.ie

Daft Reports

- Ronan Lyons (House Price, Q1 2024)

- Ronan Lyons (Rental Price, Q4 2023)

- Ronan Lyons (House Price, Q4 2023)

- Ronan Lyons (Rental Price, Q3 2023)

- Ronan Lyons (House Price, Q3 2023)

- Ronan Lyons (Rental Price, Q2 2023)

- Ronan Lyons (House Price, Q2 2023)

- Ronan Lyons (Rental Price, Q1 2023)

- Ronan Lyons (House Price, Q1 2023)

- Ronan Lyons (Rental Price, Q4 2022)

- Ronan Lyons (House Price, Q4 2022)

- Ronan Lyons (Rental Price, Q3 2022)

- Ronan Lyons (House Price, Q3 2022)

- Ronan Lyons (Rental Price, Q2 2022)

- Ronan Lyons (House Price, Q2 2022)

- Ronan Lyons (Rental Price, Q1 2022)

- Ronan Lyons (House Price, Q1 2022)

- Ronan Lyons (Rental, Q4 2021)

- Ronan Lyons (House Price, Q4 2021)

- Ronan Lyons (Rental, Q3 2021)

- Ronan Lyons (House Price, Q3 2021)

- Ronan Lyons (Rental, Q2 2021)

- Ronan Lyons (House Price, Q2 2021)

- Ronan Lyons (Rental, Q1 2021)

- Ronan Lyons (House Price, Q1 2021)

- Ronan Lyons (Rental, Q4 2020)

- Ronan Lyons (House Price, Q4 2020)

- Ronan Lyons (Wealth, H2 2020)

- Ronan Lyons (Rental, Q3 2020)

- Ronan Lyons (House Price, Q3 2020)

- Ronan Lyons (Housing, July 2020)

- Ronan Lyons (Housing, June 2020)

- Ronan Lyons (Housing, May 2020)

- Ronan Lyons (Rental, Q1 2020)

- Ronan Lyons (House Price, Q1 2020)

- Ronan Lyons (Rental, Q4 2019)

- Ronan Lyons (House Price, Q4 2019)

- Ronan Lyons (Wealth, H2 2019)

- Ronan Lyons (Rental, Q3 2019)

- Ronan Lyons (House Price, Q3 2019)

- Pierre Yimbog (Rental, Q2 2019)

- Ronan Lyons (House Price, Q2 2019)

- Ronan Lyons (Wealth, H1 2019)

- Ronan Lyons (Rental, Q1 2019)

- Ronan Lyons (House Price, Q1 2019)

- Ronan Lyons (Rental, Q4 2018)

- Ronan Lyons (House Price, Q4 2018)

- Ronan Lyons (Wealth, H2 2018)

- Ronan Lyons (Rental, Q3 2018)

- Ronan Lyons (House Price, Q3 2018)

- Shane De Rís (Rental, Q2 2018)

- Ronan Lyons (House Price, Q2 2018)

- Ronan Lyons (Wealth, 2018)

- Ronan Lyons (Rental, Q1 2018)

- Ronan Lyons (House Price, Q1 2018)

- Ronan Lyons (Rental, Q4 2017)

- Ronan Lyons (House Price, Q4 2017)

- Ronan Lyons (Rental, Q3 2017)

- Ronan Lyons (House Price, Q3 2017)

- Katie Ascough (Rental, Q2 2017)

- Ronan Lyons (Wealth, 2017)

- Ronan Lyons (House Price, Q2 2017)

- Ronan Lyons (Rental, Q1 2017)

- Ronan Lyons (House Price, Q1 2017)

- Ronan Lyons (Rental, Q4 2016)

- Ronan Lyons (House Price, Q4 2016)

- Ronan Lyons (Rental, Q3 2016)

- Ronan Lyons (House Price, Q3 2016)

- Ronan Lyons (School Report, 2016)

- Conor Viscardi (Rental, Q2 2016)

- Ronan Lyons (Rail Report, 2016)

- Ronan Lyons (House Price, Q2 2016)

- Ronan Lyons (Rental, Q1 2016)

- Ronan Lyons (House Price, Q1 2016)

- Ronan Lyons (Rental, Q4 2015)

- Ronan Lyons (House Price, Q4 2015)

- Ronan Lyons (Rental, Q3 2015)

- Ronan Lyons (House Price, Q3 2015)

- Marcus O'Halloran (Rental, Q2 2015)

- Ronan Lyons (House Price, Q2 2015)

- Ronan Lyons (Rental, Q1 2015)

- Ronan Lyons (House Price, Q1 2015)

- Ronan Lyons (Rental, Q4 2014)

- Ronan Lyons (House Price, Q4 2014)

- Ronan Lyons (Rental, Q3 2014)

- Ronan Lyons (House Price, Q3 2014)

- Domhnall McGlacken-Byrne (Rental, Q2 2014)

- Ronan Lyons (House Price, Q2 2014)

- Ronan Lyons (Rental, Q1 2014)

- Ronan Lyons (House Price, Q1 2014)

- Ronan Lyons (Rental, Q4 2013)

- Ronan Lyons (House Price, Q4 2013)

- Ronan Lyons (Rental, Q3 2013)

- Ronan Lyons (House Price, Q3 2013)

- Ronan Lyons (Rental, Q2 2013)

- Ronan Lyons (House Price, Q2 2013)

- Ronan Lyons (Rental, Q1 2013)

- Ronan Lyons (House Price, Q1 2013)

- Ronan Lyons (Rental, Q4 2012)

- Ronan Lyons (House Price, Q4 2012)

- Lorcan Sirr (Rental, Q3 2012)

- Padraic Kenna (House Price, Q3 2012)

- John Logue (Rental, Q2 2012)

- Ronan Lyons (House Price, Q2 2012)

- Barry O'Leary (Rental, Q1 2012)

- Seamus Coffey (House Price, Q1 2012)

- Joan Burton (Rental, Q4 2011)

- Ronan Lyons (House Price, Q4 2011)

- Philip O'Sullivan (Rental, Q3 2011)

- Sheila O'Flanagan (House Price, Q3 2011)

- Rachel Breslin (Rental, Q2 2011)

- Constantin Gurdgiev (House Price, Q2 2011)

- Cormac Lucey (Rental, Q1 2011)

- Eoin Fahy (House Price, Q1 2011)

- Lorcan Roche Kelly (Rental, Q4 2010)

- Ronan Lyons (House Price, Q4 2010)

- John Fitzgerald (Rental, Q3 2010)

- Patrick Koucheravy (House Price, Q3 2010)

- Gary Redmond (Rental, Q2 2010)

- Jim Power (House Price, Q2 2010)

- Jill Kerby (Rental, Q1 2010)

- Brian Lucey (House Price, Q1 2010)

- Michael Taft (Rental, Q4 2009)

- Alan McQuaid (House Price, Q4 2009)

- Dr. Charles J. Larkin (Rental, Q3 2009)

- Emer O'Siochru (House Price, Q3 2009)

- Ronan Lyons (Rental, Q2 2009)

- Oliver Gilvarry (House Price, Q2 2009)

- Brian Devine (Rental, Q1 2009)

- Dr. Liam Delaney (House Price, Q1 2009)

- Gerard O'Neill (Rental, Q4 2008)

- Ronan Lyons (House Price, Q4 2008)

- Dr. Stephen Kinsella (Rental, Q3 2008)

- Moore McDowell (House Price, Q3 2008)

- Shane Kelly (Rental, Q2 2008)

- Fergal O'Brien (House Price, Q2 2008)

- Eoin O'Sullivan (Rental, Q1 2008)

- Dermot O'Leary (House Price, Q1 2008)

- Dan O'Brien (Rental, Q4 2007)

- Frances Ruane (House Price, Q4 2007)

- John McCartney (Rental, Q3 2007)

- Ronnie O'Toole (House Price, Q3 2007)

- Ronan Lyons (Rental, Q2 2007)

- Constantin Gurdgiev (House Price, Q2 2007)

- Fintan McNamara (Rental, Q1 2007)

- Rossa White (House Price, Q1 2007)

- Geoff Tucker (Rental, Q4 2006)

- Damien Kiberd (House Price, Q4 2006)

- Pat McArdle (House Price, Q3 2006)

- Marc Coleman (House Price, Q2 2006)

- David Duffy (House Price, Q1 2006)

- Austin Hughes (House Price, Q4 2005)

- David McWilliams (House Price, Q2 2005)

9th Nov 2020

Supply does its job - in Dublin, at least

For the 2010s, the mantra in the rental market was 'supply, supply, supply'. With growing demand - both in terms of underlying need and in terms of market demand, thanks to a strong economic recovery, Ireland experienced what can only be described a lost decade, in terms of rental supply. This was largely down to very high construction costs compared to household incomes.

To take the case of Dublin, this was a city of 1.5 million people, and growing at a pace faster than almost all its peers in Europe, in which almost no new rental homes were built between 2010 and 2020. The problems were not restricted to Dublin, of course. Summing up over the four next largest cities - Cork, Limerick, Galway and Waterford - there were just 250 homes listed on the rental market at the start of 2020, barely one tenth of the stock on the market a decade earlier.

The results of such a lack of supply were entirely unsurprising if socially and economically harmful. Urban rents in Ireland have doubled from their low point early in the 2010s - as did rents in Dublin's commuter counties. Even in places further away from centres of employment, rents rose very strongly, with the smallest increase by late 2019 almost 40% (in Donegal) and the average increase for Ireland, outside the five main cities, was still 75%.

Despite the obviousness of the problem - growing demand creates a need for growing supply - it is a testament to how important housing is as a service, a fundamental human need, that Ireland's housing crisis became an ideological Rorschach test. For Ireland's relatively small cohort of anti-immigrant activists, rising rents were a surefire sign that Ireland was bursting at the seams - despite the fact that even with zero migration, Ireland would still need tens of thousands of rental homes built to match its internal demographics.

For those who see markets and profits as problematic, Ireland's housing woes were proof that markets cannot solve housing - even though the lack of housing built in the 2010s is almost entirely a policy failure (or set of them), not a market one. Ironically, the best evidence of that is when policy solutions did come and supply responded almost immediately. The most acute shortages of housing in Ireland are for housing in or close to the main cities, and for smaller households (of one- to two-persons). When policymakers addressed this, by implementing the Build-to-Rent guidelines, many of the commentators arguing that markets were unreliable as they would never create the supply needed switched overnight to criticisms of for-profit developers channeling European pension funds to build the homes that Ireland needs.

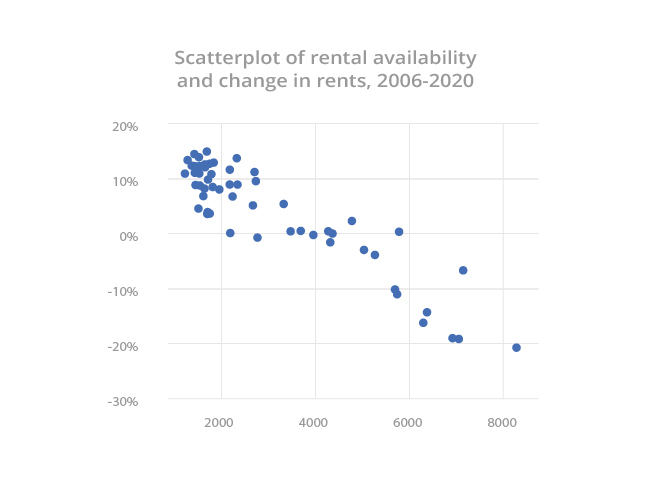

The graph accompanying this piece shows more powerfully than any commentary can, though, just how important supply is. The horizontal axis shows the number of properties listed for rent on the first day of every quarter from 2006 until 2020, while the vertical axis shows how rents that quarter compared to a year ago. The link is obvious: the more homes there are available to rent at a given point in time, the less upward pressure there is on rents. Indeed, when there are more than 4,000 properties available to rent in Dublin, there is downward pressure on rents. The same holds true for other rental markets around the country.

This is the backdrop for the figures contained in this latest Daft.ie Rental Report. It finds that rents across the country continue to rise - with the notable exception of Dublin, where rents are falling. What explains these trends is, hopefully given the above, unsurprising. In most parts of the country, the stock of homes available to rent continues to fall and is at all-time or close to all-time lows, in series stretching back to January 2006. In Dublin, however, availability has doubled in the last year - and with it, rental inflation has come to an end.

The glut in Dublin supply does not, however, signal that policymakers can 'take the pedal off' and congratulate themselves on a job well done. Indeed, if anything, the journey to fixing Ireland's deficient rental supply has barely started. Only about 35,000 rental homes are currently either in construction or on the plans - and almost all of those are in Dublin.

The respite in Dublin's rental sector is down to Covid-19, which has brought about a once-off redistribution of a couple of thousand properties from the short-term lettings segment to the long-term rental segment. As welcome as these are for those now living in them, they are a finite resource and that, combined with depressed migration into the city, has meant that rents in the third quarter of 2020 were 0.8% lower than a year previously, the first time in almost a decade that rents fell in the capital.

Much has been made of how Covid-19 has the potential to rewrite the rules of the housing market - both sale and rental. A lot of this seems, once more, to be something akin to a Rorschach test. Those who always pined for 'balanced regional development' see it as likely to reduce the 'Dublin premium'. Those who never liked one-beds, student accommodation or co-living - despite the cities' need for such homes - are convinced that Covid has proven them right all along.

However, the data do not back up these assertions - at least not yet. If anything, housing markets (both sale and rental) in Ireland's second-tier cities have performed the most strongly this year. But if we compare the average rent in Dublin to, say, Connacht-Ulster (outside Galway city), the premium of 164% in 2020Q3 is slightly above that in 2019Q3 and pretty much in line with the premiums in other recent years. (Dublin's rental premium relative to the four other cities has fallen from 60% pre-Covid to 50% in the latest report.)

When it comes to smaller homes, if Covid-19 is having an effect, it is the opposite of the one some pundits expected. Compared to a three-bed with five other students, or a four-bed with three other young professionals, a one-bedroom apartment sounds distinctly more sanitary - as do purpose-built student and co-living blocks. The data in this report seem to back this up, with the discount for a one-bedroom apartment falling slowly but steadily from 35% pre-Covid to 32% in the latest report.