Irish House Price Report Q3 2019 | Daft.ie

Daft Reports

- Ronan Lyons (House Price, Q1 2024)

- Ronan Lyons (Rental Price, Q4 2023)

- Ronan Lyons (House Price, Q4 2023)

- Ronan Lyons (Rental Price, Q3 2023)

- Ronan Lyons (House Price, Q3 2023)

- Ronan Lyons (Rental Price, Q2 2023)

- Ronan Lyons (House Price, Q2 2023)

- Ronan Lyons (Rental Price, Q1 2023)

- Ronan Lyons (House Price, Q1 2023)

- Ronan Lyons (Rental Price, Q4 2022)

- Ronan Lyons (House Price, Q4 2022)

- Ronan Lyons (Rental Price, Q3 2022)

- Ronan Lyons (House Price, Q3 2022)

- Ronan Lyons (Rental Price, Q2 2022)

- Ronan Lyons (House Price, Q2 2022)

- Ronan Lyons (Rental Price, Q1 2022)

- Ronan Lyons (House Price, Q1 2022)

- Ronan Lyons (Rental, Q4 2021)

- Ronan Lyons (House Price, Q4 2021)

- Ronan Lyons (Rental, Q3 2021)

- Ronan Lyons (House Price, Q3 2021)

- Ronan Lyons (Rental, Q2 2021)

- Ronan Lyons (House Price, Q2 2021)

- Ronan Lyons (Rental, Q1 2021)

- Ronan Lyons (House Price, Q1 2021)

- Ronan Lyons (Rental, Q4 2020)

- Ronan Lyons (House Price, Q4 2020)

- Ronan Lyons (Wealth, H2 2020)

- Ronan Lyons (Rental, Q3 2020)

- Ronan Lyons (House Price, Q3 2020)

- Ronan Lyons (Housing, July 2020)

- Ronan Lyons (Housing, June 2020)

- Ronan Lyons (Housing, May 2020)

- Ronan Lyons (Rental, Q1 2020)

- Ronan Lyons (House Price, Q1 2020)

- Ronan Lyons (Rental, Q4 2019)

- Ronan Lyons (House Price, Q4 2019)

- Ronan Lyons (Wealth, H2 2019)

- Ronan Lyons (Rental, Q3 2019)

- Ronan Lyons (House Price, Q3 2019)

- Pierre Yimbog (Rental, Q2 2019)

- Ronan Lyons (House Price, Q2 2019)

- Ronan Lyons (Wealth, H1 2019)

- Ronan Lyons (Rental, Q1 2019)

- Ronan Lyons (House Price, Q1 2019)

- Ronan Lyons (Rental, Q4 2018)

- Ronan Lyons (House Price, Q4 2018)

- Ronan Lyons (Wealth, H2 2018)

- Ronan Lyons (Rental, Q3 2018)

- Ronan Lyons (House Price, Q3 2018)

- Shane De Rís (Rental, Q2 2018)

- Ronan Lyons (House Price, Q2 2018)

- Ronan Lyons (Wealth, 2018)

- Ronan Lyons (Rental, Q1 2018)

- Ronan Lyons (House Price, Q1 2018)

- Ronan Lyons (Rental, Q4 2017)

- Ronan Lyons (House Price, Q4 2017)

- Ronan Lyons (Rental, Q3 2017)

- Ronan Lyons (House Price, Q3 2017)

- Katie Ascough (Rental, Q2 2017)

- Ronan Lyons (Wealth, 2017)

- Ronan Lyons (House Price, Q2 2017)

- Ronan Lyons (Rental, Q1 2017)

- Ronan Lyons (House Price, Q1 2017)

- Ronan Lyons (Rental, Q4 2016)

- Ronan Lyons (House Price, Q4 2016)

- Ronan Lyons (Rental, Q3 2016)

- Ronan Lyons (House Price, Q3 2016)

- Ronan Lyons (School Report, 2016)

- Conor Viscardi (Rental, Q2 2016)

- Ronan Lyons (Rail Report, 2016)

- Ronan Lyons (House Price, Q2 2016)

- Ronan Lyons (Rental, Q1 2016)

- Ronan Lyons (House Price, Q1 2016)

- Ronan Lyons (Rental, Q4 2015)

- Ronan Lyons (House Price, Q4 2015)

- Ronan Lyons (Rental, Q3 2015)

- Ronan Lyons (House Price, Q3 2015)

- Marcus O'Halloran (Rental, Q2 2015)

- Ronan Lyons (House Price, Q2 2015)

- Ronan Lyons (Rental, Q1 2015)

- Ronan Lyons (House Price, Q1 2015)

- Ronan Lyons (Rental, Q4 2014)

- Ronan Lyons (House Price, Q4 2014)

- Ronan Lyons (Rental, Q3 2014)

- Ronan Lyons (House Price, Q3 2014)

- Domhnall McGlacken-Byrne (Rental, Q2 2014)

- Ronan Lyons (House Price, Q2 2014)

- Ronan Lyons (Rental, Q1 2014)

- Ronan Lyons (House Price, Q1 2014)

- Ronan Lyons (Rental, Q4 2013)

- Ronan Lyons (House Price, Q4 2013)

- Ronan Lyons (Rental, Q3 2013)

- Ronan Lyons (House Price, Q3 2013)

- Ronan Lyons (Rental, Q2 2013)

- Ronan Lyons (House Price, Q2 2013)

- Ronan Lyons (Rental, Q1 2013)

- Ronan Lyons (House Price, Q1 2013)

- Ronan Lyons (Rental, Q4 2012)

- Ronan Lyons (House Price, Q4 2012)

- Lorcan Sirr (Rental, Q3 2012)

- Padraic Kenna (House Price, Q3 2012)

- John Logue (Rental, Q2 2012)

- Ronan Lyons (House Price, Q2 2012)

- Barry O'Leary (Rental, Q1 2012)

- Seamus Coffey (House Price, Q1 2012)

- Joan Burton (Rental, Q4 2011)

- Ronan Lyons (House Price, Q4 2011)

- Philip O'Sullivan (Rental, Q3 2011)

- Sheila O'Flanagan (House Price, Q3 2011)

- Rachel Breslin (Rental, Q2 2011)

- Constantin Gurdgiev (House Price, Q2 2011)

- Cormac Lucey (Rental, Q1 2011)

- Eoin Fahy (House Price, Q1 2011)

- Lorcan Roche Kelly (Rental, Q4 2010)

- Ronan Lyons (House Price, Q4 2010)

- John Fitzgerald (Rental, Q3 2010)

- Patrick Koucheravy (House Price, Q3 2010)

- Gary Redmond (Rental, Q2 2010)

- Jim Power (House Price, Q2 2010)

- Jill Kerby (Rental, Q1 2010)

- Brian Lucey (House Price, Q1 2010)

- Michael Taft (Rental, Q4 2009)

- Alan McQuaid (House Price, Q4 2009)

- Dr. Charles J. Larkin (Rental, Q3 2009)

- Emer O'Siochru (House Price, Q3 2009)

- Ronan Lyons (Rental, Q2 2009)

- Oliver Gilvarry (House Price, Q2 2009)

- Brian Devine (Rental, Q1 2009)

- Dr. Liam Delaney (House Price, Q1 2009)

- Gerard O'Neill (Rental, Q4 2008)

- Ronan Lyons (House Price, Q4 2008)

- Dr. Stephen Kinsella (Rental, Q3 2008)

- Moore McDowell (House Price, Q3 2008)

- Shane Kelly (Rental, Q2 2008)

- Fergal O'Brien (House Price, Q2 2008)

- Eoin O'Sullivan (Rental, Q1 2008)

- Dermot O'Leary (House Price, Q1 2008)

- Dan O'Brien (Rental, Q4 2007)

- Frances Ruane (House Price, Q4 2007)

- John McCartney (Rental, Q3 2007)

- Ronnie O'Toole (House Price, Q3 2007)

- Ronan Lyons (Rental, Q2 2007)

- Constantin Gurdgiev (House Price, Q2 2007)

- Fintan McNamara (Rental, Q1 2007)

- Rossa White (House Price, Q1 2007)

- Geoff Tucker (Rental, Q4 2006)

- Damien Kiberd (House Price, Q4 2006)

- Pat McArdle (House Price, Q3 2006)

- Marc Coleman (House Price, Q2 2006)

- David Duffy (House Price, Q1 2006)

- Austin Hughes (House Price, Q4 2005)

- David McWilliams (House Price, Q2 2005)

The figures from this latest Daft.ie Housing Report show that the prolonged increase in housing prices is, in many parts of the country and for the time being at least, over. Inflation in listed housing prices nationwide was just 0.1% in the third quarter of 2019, while in Dublin inflation was negative, with prices 0.6% lower than a year previously.*

This end of inflation, at least for the moment, marks the culmination of a trend highlighted seven reports ago. Steadily, if somewhat evenly around the country, inflation in housing prices has been easing since mid-2017. This became noticeable in early 2018 and in my commentary on the 2018 Q2 report, I wrote: "Scratch a little bit beneath the surface and there are hints that the picture is slowly changing... supply is slowly but surely coming on stream."

This prediction has been borne out in subsequent reports - not just those by Daft.ie but also other reports on housing prices and, critically, housing supply. There are two different ways of measuring housing supply. The first is what is actively on the market - this is the availability part of supply. The second is what is being built - this is the construction part of supply.

In terms of availability, the change in conditions is most clearly seen in Dublin. In early 2017, there were just over 2,500 homes actively for sale in Dublin. By mid-2019, that had more than doubled, with 5,400 homes for sale over the summer in Dublin. This was further supported by trends in Dublin's commuter counties, where the number of homes actively for sale increase by roughly one thousand, to 3,200, over the same period.

In fact, it is more accurate to say that improved availability is entire a Greater Dublin Area (GDA) phenomenon. Elsewhere in the country, there has been remarkable stability in the number of homes for sale over the last three years. In early 2017, there were roughly 16,000 homes for sale outside the GDA. In mid-2019, the figure was almost identical.

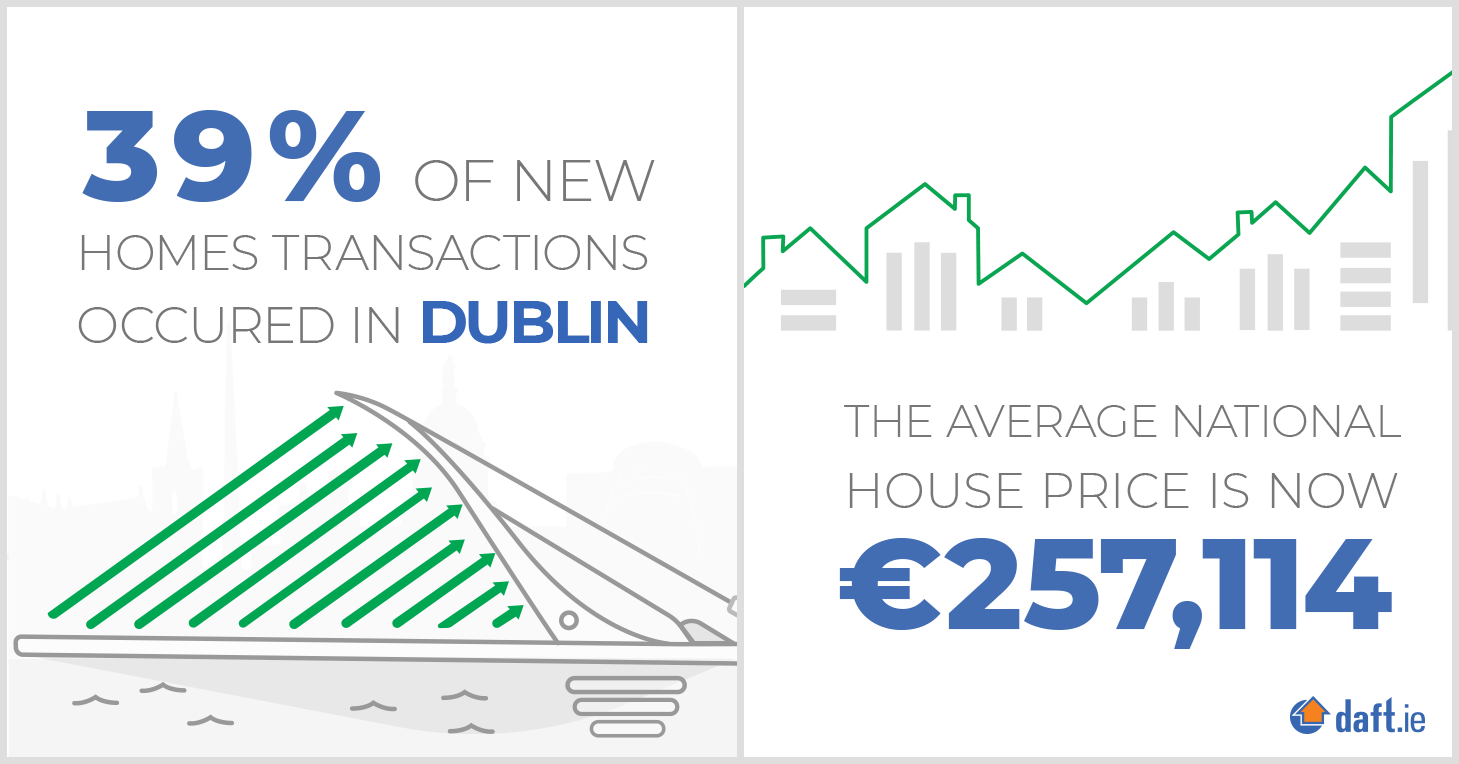

This change in availability is, ultimately, driven by construction. There were almost 20,000 homes built between the middle of 2018 and the middle of 2019, twice the number built during the twelve months of 2016. Just under two thirds of that increase in building activity has been in the Greater Dublin Area and, for the moment at least, the new homes built have been concentrated in the owner-occupied sector.

But new housing supply is not the full story of what's going on. The elephant in the room, for the Irish economy, is Brexit. To understand how that something that has not happened yet could affect housing prices now, it is important to remember a key difference between the sale and rental segments.

Across both segments, fundamentals of supply and demand matter. If more homes are built for a particular segment, this will lower prices everything else being equal. If incomes rise or if the numbers at work increase, this will increase prices, both sale and rental. However, for sale properties, the purchaser is committing to hold the asset and thus they have to pay attention to its future value too. This difference also means that credit is prevalent in the for-sale market, due to its much higher price level, but not the rental market.

Therefore, both credit conditions and expectations about future prices are key factors in converting 'real demand' into effective 'on the ground' demand in the sales market. If Brexit, in whatever form it takes, reduces Irish employment and incomes, this will be seen in the rental market. If Brexit is expected to affect Irish employment and incomes in the future, this will be seen in the sales market.

Disentangling between the increase in supply, what might be termed a healthy slowdown in housing prices, and an expected economic shock, what a reasonable person might call a worrying slowdown in prices, is not trivial. One piece of evidence comes from the Dublin market. Underpinning the results of the Daft.ie Report are 117 micro-markets in the Dublin itself, where average prices vary from almost €875,000 to below €200,000.

Dublin has 30 of the micro-markets where average prices a year ago were above €500,000. Those are the markets where new supply is most viable, as construction costs are not an impediment to those with sites. Those top-tier markets have seen prices fall by an average of 2.5% in the last year, with the most expensive four markets all seeing prices fall by 10% or more in 12 months.

At the other end of the spectrum, there were 34 markets where prices a year ago were €300,000 or lower. In these, new construction is less likely as viability is a major challenge for developers, and in across these markets, there was an average change of zero in prices over the last year. (This hides some variation, incidentally, with one market seeing prices rise by 9% and another saw falls of 5%).

Those figures from the Dublin market are more consistent with supply affecting prices than with Brexit freezing the market. That is not to say, of course, that Brexit is not having an effect. One need only look at micro-markets close to the border to see that. In Buncrana, prices are down 17% year-on-year, as they are around Cootehill in Cavan. Prices are also falling in the north-east of Louth, close to the border.

Brexit may not be the story of the housing market yet, but it may very well dominate the market over coming reports. For the moment, though, the cooling of the market reflects supply of homeowner properties matching effective demand. It is, therefore, a good news story not a bad one.

*All price figures in this report are based on analysis up to mid-September and are subject to revision and finalization in the Q4 report.