Irish House Price Report Q3 2022 | Daft.ie

Daft Reports

- Ronan Lyons (House Price, Q1 2024)

- Ronan Lyons (Rental Price, Q4 2023)

- Ronan Lyons (House Price, Q4 2023)

- Ronan Lyons (Rental Price, Q3 2023)

- Ronan Lyons (House Price, Q3 2023)

- Ronan Lyons (Rental Price, Q2 2023)

- Ronan Lyons (House Price, Q2 2023)

- Ronan Lyons (Rental Price, Q1 2023)

- Ronan Lyons (House Price, Q1 2023)

- Ronan Lyons (Rental Price, Q4 2022)

- Ronan Lyons (House Price, Q4 2022)

- Ronan Lyons (Rental Price, Q3 2022)

- Ronan Lyons (House Price, Q3 2022)

- Ronan Lyons (Rental Price, Q2 2022)

- Ronan Lyons (House Price, Q2 2022)

- Ronan Lyons (Rental Price, Q1 2022)

- Ronan Lyons (House Price, Q1 2022)

- Ronan Lyons (Rental, Q4 2021)

- Ronan Lyons (House Price, Q4 2021)

- Ronan Lyons (Rental, Q3 2021)

- Ronan Lyons (House Price, Q3 2021)

- Ronan Lyons (Rental, Q2 2021)

- Ronan Lyons (House Price, Q2 2021)

- Ronan Lyons (Rental, Q1 2021)

- Ronan Lyons (House Price, Q1 2021)

- Ronan Lyons (Rental, Q4 2020)

- Ronan Lyons (House Price, Q4 2020)

- Ronan Lyons (Wealth, H2 2020)

- Ronan Lyons (Rental, Q3 2020)

- Ronan Lyons (House Price, Q3 2020)

- Ronan Lyons (Housing, July 2020)

- Ronan Lyons (Housing, June 2020)

- Ronan Lyons (Housing, May 2020)

- Ronan Lyons (Rental, Q1 2020)

- Ronan Lyons (House Price, Q1 2020)

- Ronan Lyons (Rental, Q4 2019)

- Ronan Lyons (House Price, Q4 2019)

- Ronan Lyons (Wealth, H2 2019)

- Ronan Lyons (Rental, Q3 2019)

- Ronan Lyons (House Price, Q3 2019)

- Pierre Yimbog (Rental, Q2 2019)

- Ronan Lyons (House Price, Q2 2019)

- Ronan Lyons (Wealth, H1 2019)

- Ronan Lyons (Rental, Q1 2019)

- Ronan Lyons (House Price, Q1 2019)

- Ronan Lyons (Rental, Q4 2018)

- Ronan Lyons (House Price, Q4 2018)

- Ronan Lyons (Wealth, H2 2018)

- Ronan Lyons (Rental, Q3 2018)

- Ronan Lyons (House Price, Q3 2018)

- Shane De Rís (Rental, Q2 2018)

- Ronan Lyons (House Price, Q2 2018)

- Ronan Lyons (Wealth, 2018)

- Ronan Lyons (Rental, Q1 2018)

- Ronan Lyons (House Price, Q1 2018)

- Ronan Lyons (Rental, Q4 2017)

- Ronan Lyons (House Price, Q4 2017)

- Ronan Lyons (Rental, Q3 2017)

- Ronan Lyons (House Price, Q3 2017)

- Katie Ascough (Rental, Q2 2017)

- Ronan Lyons (Wealth, 2017)

- Ronan Lyons (House Price, Q2 2017)

- Ronan Lyons (Rental, Q1 2017)

- Ronan Lyons (House Price, Q1 2017)

- Ronan Lyons (Rental, Q4 2016)

- Ronan Lyons (House Price, Q4 2016)

- Ronan Lyons (Rental, Q3 2016)

- Ronan Lyons (House Price, Q3 2016)

- Ronan Lyons (School Report, 2016)

- Conor Viscardi (Rental, Q2 2016)

- Ronan Lyons (Rail Report, 2016)

- Ronan Lyons (House Price, Q2 2016)

- Ronan Lyons (Rental, Q1 2016)

- Ronan Lyons (House Price, Q1 2016)

- Ronan Lyons (Rental, Q4 2015)

- Ronan Lyons (House Price, Q4 2015)

- Ronan Lyons (Rental, Q3 2015)

- Ronan Lyons (House Price, Q3 2015)

- Marcus O'Halloran (Rental, Q2 2015)

- Ronan Lyons (House Price, Q2 2015)

- Ronan Lyons (Rental, Q1 2015)

- Ronan Lyons (House Price, Q1 2015)

- Ronan Lyons (Rental, Q4 2014)

- Ronan Lyons (House Price, Q4 2014)

- Ronan Lyons (Rental, Q3 2014)

- Ronan Lyons (House Price, Q3 2014)

- Domhnall McGlacken-Byrne (Rental, Q2 2014)

- Ronan Lyons (House Price, Q2 2014)

- Ronan Lyons (Rental, Q1 2014)

- Ronan Lyons (House Price, Q1 2014)

- Ronan Lyons (Rental, Q4 2013)

- Ronan Lyons (House Price, Q4 2013)

- Ronan Lyons (Rental, Q3 2013)

- Ronan Lyons (House Price, Q3 2013)

- Ronan Lyons (Rental, Q2 2013)

- Ronan Lyons (House Price, Q2 2013)

- Ronan Lyons (Rental, Q1 2013)

- Ronan Lyons (House Price, Q1 2013)

- Ronan Lyons (Rental, Q4 2012)

- Ronan Lyons (House Price, Q4 2012)

- Lorcan Sirr (Rental, Q3 2012)

- Padraic Kenna (House Price, Q3 2012)

- John Logue (Rental, Q2 2012)

- Ronan Lyons (House Price, Q2 2012)

- Barry O'Leary (Rental, Q1 2012)

- Seamus Coffey (House Price, Q1 2012)

- Joan Burton (Rental, Q4 2011)

- Ronan Lyons (House Price, Q4 2011)

- Philip O'Sullivan (Rental, Q3 2011)

- Sheila O'Flanagan (House Price, Q3 2011)

- Rachel Breslin (Rental, Q2 2011)

- Constantin Gurdgiev (House Price, Q2 2011)

- Cormac Lucey (Rental, Q1 2011)

- Eoin Fahy (House Price, Q1 2011)

- Lorcan Roche Kelly (Rental, Q4 2010)

- Ronan Lyons (House Price, Q4 2010)

- John Fitzgerald (Rental, Q3 2010)

- Patrick Koucheravy (House Price, Q3 2010)

- Gary Redmond (Rental, Q2 2010)

- Jim Power (House Price, Q2 2010)

- Jill Kerby (Rental, Q1 2010)

- Brian Lucey (House Price, Q1 2010)

- Michael Taft (Rental, Q4 2009)

- Alan McQuaid (House Price, Q4 2009)

- Dr. Charles J. Larkin (Rental, Q3 2009)

- Emer O'Siochru (House Price, Q3 2009)

- Ronan Lyons (Rental, Q2 2009)

- Oliver Gilvarry (House Price, Q2 2009)

- Brian Devine (Rental, Q1 2009)

- Dr. Liam Delaney (House Price, Q1 2009)

- Gerard O'Neill (Rental, Q4 2008)

- Ronan Lyons (House Price, Q4 2008)

- Dr. Stephen Kinsella (Rental, Q3 2008)

- Moore McDowell (House Price, Q3 2008)

- Shane Kelly (Rental, Q2 2008)

- Fergal O'Brien (House Price, Q2 2008)

- Eoin O'Sullivan (Rental, Q1 2008)

- Dermot O'Leary (House Price, Q1 2008)

- Dan O'Brien (Rental, Q4 2007)

- Frances Ruane (House Price, Q4 2007)

- John McCartney (Rental, Q3 2007)

- Ronnie O'Toole (House Price, Q3 2007)

- Ronan Lyons (Rental, Q2 2007)

- Constantin Gurdgiev (House Price, Q2 2007)

- Fintan McNamara (Rental, Q1 2007)

- Rossa White (House Price, Q1 2007)

- Geoff Tucker (Rental, Q4 2006)

- Damien Kiberd (House Price, Q4 2006)

- Pat McArdle (House Price, Q3 2006)

- Marc Coleman (House Price, Q2 2006)

- David Duffy (House Price, Q1 2006)

- Austin Hughes (House Price, Q4 2005)

- David McWilliams (House Price, Q2 2005)

26th Sep 2022

What would a healthy housing system look like?

This is quite the question for anyone who has had to endure the vicissitudes of Ireland's housing system over the last few years and indeed the generation. As I've written in past reports, ultimately the challenge facing the Irish housing system is that, once Ireland found a successful business model once more in the 1990s ‐ after 150 years without one ‐ the country was unable to accommodate the growth unleashed in the labour market.

With post-Celtic Tiger net migration at an all-time high in the year to 2022, this growth shows no signs of abating. Indeed, preliminary Census 2022 figures indicate that underlying housing need in Ireland over the coming three decades is likely to be in the range of 42,000 to 62,000 homes, not far off twice the underlying level of 28,000 new homes per year that underpins Housing For All, launched as recently as 2020.

This year, Ireland may see 25,000 new homes completed ‐ and as things stand, the most optimistic forecasts for next year are that this total would be matched. This is in part because construction costs have increased ‐ by almost 15% in a single year, according to the SCSI's latest figures ‐ and in part because, since 2018, Ireland's planning system has effectively become embedded in Ireland's legal system, slowing down the conversion rate from permissions granted to building started.

All of that is a round-about way of saying that the health of Ireland's housing system is ultimately measured by how responsive supply, of all forms (not just for-profit development), is to demand (again of all forms). There are few who would argue against the assessment that Ireland's housing system has been unhealthy for at least the last seven years and I would argue that this failure extends back to the 1990s, albeit with an exception for rural housing, induced by tax reliefs, during the Celtic Tiger years.

But a bird's-eye view is just that: it's a high-level assessment of homes needed given the way we live. Breaking it down into, to start, the three main segments ‐ sales, market rental, and social rental ‐ we need other measures of health and indeed other measures of supply.

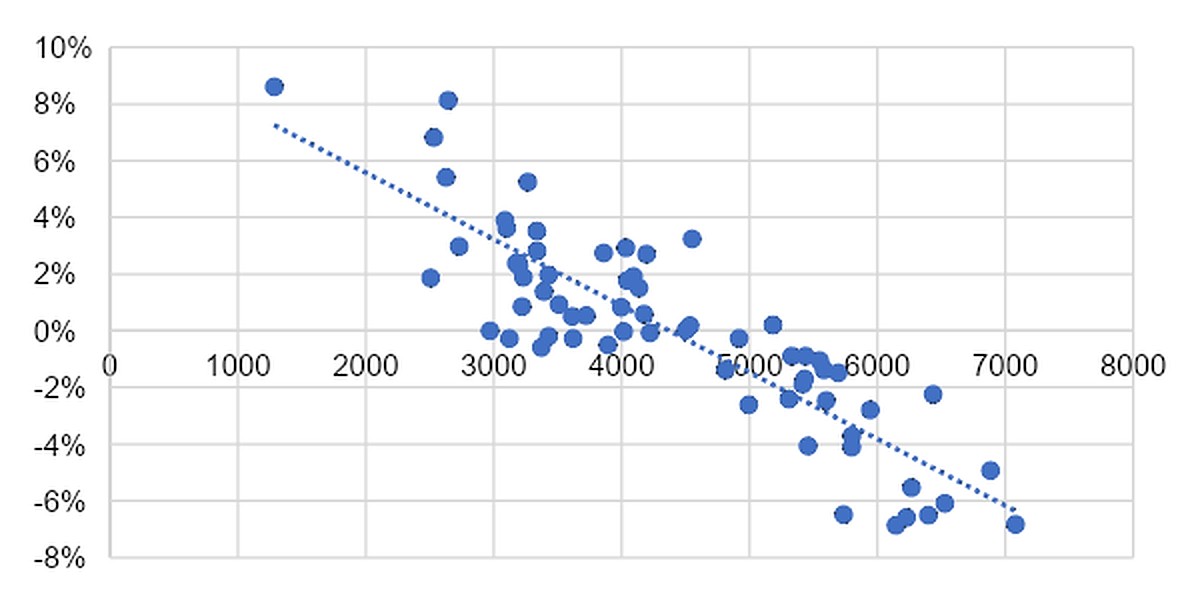

One that is easy to monitor and, it turns out, relatively reliable is the number of homes available on the market at any one time. The figure accompanying this piece shows, for the Dublin market, the total number of homes available on the first day of each quarter on Daft.ie, from the start of 2006 to the middle of 2022, and the subsequent quarterly change in prices, as measured in the Daft.ie Report (which controls for the mix of type and location).

I've included on the graph something called the R-squared ‐ this is basically a measure of fit. The closer to 100% it is, the more closely the two move together. An R-squared of over 76% is very high, implying that knowing only one figure ‐ the number of homes available on the Dublin market on the first of a quarter ‐ would on average give you a good guess on what happens to prices over the coming three months.

The more homes there are on the market, the less upward pressure ‐ and more downward pressure ‐ there is on Dublin prices. This is completely in line with basic economic theory, although it is perhaps an indication of how poor the public discourse around housing is that it could be at all contentious that someone could argue that more supply will make housing more affordable.

The "magic number" ‐ such that there can ever be one ‐ is somewhere around 4,500. More homes on the market in Dublin than this, and there is likely to be some downward pressure on prices. Fewer homes, and prices are likely to rise. We can see these patterns over the last decade of the Dublin housing market ‐ and indeed extend it to look at other parts of the country.

In early 2014, the number of homes on the market in Dublin fell to just 2,300. Prices soared that year, so much so that the Central Bank brought in the mortgage rules, to avoid another bubble-crash episode. Availability more than doubled in the following year and inflation disappeared from the Dublin market for almost 18 months.

But by early 2017, stock on the market had fallen back to 2,600 and inflation spiked once more. For most of the following three years, though, availability improved and in 2019, as it averaged 5,000 homes on the market, there was a modest fall (of 1%) in Dublin prices that year. Supply was doing its job.

Covid19 completely disrupted the market and, by early 2022, once again there were just 2,700 homes on the market in Dublin and, once more, prices in the capital were rising. But over the course of the year, stock on the market has increased steadily, to over 4,000 in the third quarter of the year. And with that improvement, prices in the capital were stable in the third quarter.

Overall, availability in the Dublin market is about one third higher now than a year ago. In the rest of Leinster, it's up 40%, and while still low, it suggests an easing off in inflation, after a prolonged bout during covid19.

In the rest of the country, stock on the market remains very low compared to the average over the last 15 years. Indeed, while Dublin has seen repeated cycles in availability over the past decade, for the rest of the country, it has been a period of steady falls in availability, from extraordinary gluts in late 2010 to acute shortages in early 2022: from over 55,000 homes to just 7,300 homes in early 2022.

Availability on the market at any one time is a combination of both supply and demand: the stronger demand is, the fewer homes put up for sale in July that will still be on the market in September. We can see, from the increase in flow of properties on to the market, that improving availability reflects in part the supply side improving.

The open question for the coming months is, with interest rates rising and significant inflation in non-housing costs, for effectively the first time in 15 years, whether falling demand will play its role too.