Quantities, not prices, are where the problems lie in the Irish rental market

Daft Reports

- Ronan Lyons (House Price, Q1 2024)

- Ronan Lyons (Rental Price, Q4 2023)

- Ronan Lyons (House Price, Q4 2023)

- Ronan Lyons (Rental Price, Q3 2023)

- Ronan Lyons (House Price, Q3 2023)

- Ronan Lyons (Rental Price, Q2 2023)

- Ronan Lyons (House Price, Q2 2023)

- Ronan Lyons (Rental Price, Q1 2023)

- Ronan Lyons (House Price, Q1 2023)

- Ronan Lyons (Rental Price, Q4 2022)

- Ronan Lyons (House Price, Q4 2022)

- Ronan Lyons (Rental Price, Q3 2022)

- Ronan Lyons (House Price, Q3 2022)

- Ronan Lyons (Rental Price, Q2 2022)

- Ronan Lyons (House Price, Q2 2022)

- Ronan Lyons (Rental Price, Q1 2022)

- Ronan Lyons (House Price, Q1 2022)

- Ronan Lyons (Rental, Q4 2021)

- Ronan Lyons (House Price, Q4 2021)

- Ronan Lyons (Rental, Q3 2021)

- Ronan Lyons (House Price, Q3 2021)

- Ronan Lyons (Rental, Q2 2021)

- Ronan Lyons (House Price, Q2 2021)

- Ronan Lyons (Rental, Q1 2021)

- Ronan Lyons (House Price, Q1 2021)

- Ronan Lyons (Rental, Q4 2020)

- Ronan Lyons (House Price, Q4 2020)

- Ronan Lyons (Wealth, H2 2020)

- Ronan Lyons (Rental, Q3 2020)

- Ronan Lyons (House Price, Q3 2020)

- Ronan Lyons (Housing, July 2020)

- Ronan Lyons (Housing, June 2020)

- Ronan Lyons (Housing, May 2020)

- Ronan Lyons (Rental, Q1 2020)

- Ronan Lyons (House Price, Q1 2020)

- Ronan Lyons (Rental, Q4 2019)

- Ronan Lyons (House Price, Q4 2019)

- Ronan Lyons (Wealth, H2 2019)

- Ronan Lyons (Rental, Q3 2019)

- Ronan Lyons (House Price, Q3 2019)

- Pierre Yimbog (Rental, Q2 2019)

- Ronan Lyons (House Price, Q2 2019)

- Ronan Lyons (Wealth, H1 2019)

- Ronan Lyons (Rental, Q1 2019)

- Ronan Lyons (House Price, Q1 2019)

- Ronan Lyons (Rental, Q4 2018)

- Ronan Lyons (House Price, Q4 2018)

- Ronan Lyons (Wealth, H2 2018)

- Ronan Lyons (Rental, Q3 2018)

- Ronan Lyons (House Price, Q3 2018)

- Shane De Rís (Rental, Q2 2018)

- Ronan Lyons (House Price, Q2 2018)

- Ronan Lyons (Wealth, 2018)

- Ronan Lyons (Rental, Q1 2018)

- Ronan Lyons (House Price, Q1 2018)

- Ronan Lyons (Rental, Q4 2017)

- Ronan Lyons (House Price, Q4 2017)

- Ronan Lyons (Rental, Q3 2017)

- Ronan Lyons (House Price, Q3 2017)

- Katie Ascough (Rental, Q2 2017)

- Ronan Lyons (Wealth, 2017)

- Ronan Lyons (House Price, Q2 2017)

- Ronan Lyons (Rental, Q1 2017)

- Ronan Lyons (House Price, Q1 2017)

- Ronan Lyons (Rental, Q4 2016)

- Ronan Lyons (House Price, Q4 2016)

- Ronan Lyons (Rental, Q3 2016)

- Ronan Lyons (House Price, Q3 2016)

- Ronan Lyons (School Report, 2016)

- Conor Viscardi (Rental, Q2 2016)

- Ronan Lyons (Rail Report, 2016)

- Ronan Lyons (House Price, Q2 2016)

- Ronan Lyons (Rental, Q1 2016)

- Ronan Lyons (House Price, Q1 2016)

- Ronan Lyons (Rental, Q4 2015)

- Ronan Lyons (House Price, Q4 2015)

- Ronan Lyons (Rental, Q3 2015)

- Ronan Lyons (House Price, Q3 2015)

- Marcus O'Halloran (Rental, Q2 2015)

- Ronan Lyons (House Price, Q2 2015)

- Ronan Lyons (Rental, Q1 2015)

- Ronan Lyons (House Price, Q1 2015)

- Ronan Lyons (Rental, Q4 2014)

- Ronan Lyons (House Price, Q4 2014)

- Ronan Lyons (Rental, Q3 2014)

- Ronan Lyons (House Price, Q3 2014)

- Domhnall McGlacken-Byrne (Rental, Q2 2014)

- Ronan Lyons (House Price, Q2 2014)

- Ronan Lyons (Rental, Q1 2014)

- Ronan Lyons (House Price, Q1 2014)

- Ronan Lyons (Rental, Q4 2013)

- Ronan Lyons (House Price, Q4 2013)

- Ronan Lyons (Rental, Q3 2013)

- Ronan Lyons (House Price, Q3 2013)

- Ronan Lyons (Rental, Q2 2013)

- Ronan Lyons (House Price, Q2 2013)

- Ronan Lyons (Rental, Q1 2013)

- Ronan Lyons (House Price, Q1 2013)

- Ronan Lyons (Rental, Q4 2012)

- Ronan Lyons (House Price, Q4 2012)

- Lorcan Sirr (Rental, Q3 2012)

- Padraic Kenna (House Price, Q3 2012)

- John Logue (Rental, Q2 2012)

- Ronan Lyons (House Price, Q2 2012)

- Barry O'Leary (Rental, Q1 2012)

- Seamus Coffey (House Price, Q1 2012)

- Joan Burton (Rental, Q4 2011)

- Ronan Lyons (House Price, Q4 2011)

- Philip O'Sullivan (Rental, Q3 2011)

- Sheila O'Flanagan (House Price, Q3 2011)

- Rachel Breslin (Rental, Q2 2011)

- Constantin Gurdgiev (House Price, Q2 2011)

- Cormac Lucey (Rental, Q1 2011)

- Eoin Fahy (House Price, Q1 2011)

- Lorcan Roche Kelly (Rental, Q4 2010)

- Ronan Lyons (House Price, Q4 2010)

- John Fitzgerald (Rental, Q3 2010)

- Patrick Koucheravy (House Price, Q3 2010)

- Gary Redmond (Rental, Q2 2010)

- Jim Power (House Price, Q2 2010)

- Jill Kerby (Rental, Q1 2010)

- Brian Lucey (House Price, Q1 2010)

- Michael Taft (Rental, Q4 2009)

- Alan McQuaid (House Price, Q4 2009)

- Dr. Charles J. Larkin (Rental, Q3 2009)

- Emer O'Siochru (House Price, Q3 2009)

- Ronan Lyons (Rental, Q2 2009)

- Oliver Gilvarry (House Price, Q2 2009)

- Brian Devine (Rental, Q1 2009)

- Dr. Liam Delaney (House Price, Q1 2009)

- Gerard O'Neill (Rental, Q4 2008)

- Ronan Lyons (House Price, Q4 2008)

- Dr. Stephen Kinsella (Rental, Q3 2008)

- Moore McDowell (House Price, Q3 2008)

- Shane Kelly (Rental, Q2 2008)

- Fergal O'Brien (House Price, Q2 2008)

- Eoin O'Sullivan (Rental, Q1 2008)

- Dermot O'Leary (House Price, Q1 2008)

- Dan O'Brien (Rental, Q4 2007)

- Frances Ruane (House Price, Q4 2007)

- John McCartney (Rental, Q3 2007)

- Ronnie O'Toole (House Price, Q3 2007)

- Ronan Lyons (Rental, Q2 2007)

- Constantin Gurdgiev (House Price, Q2 2007)

- Fintan McNamara (Rental, Q1 2007)

- Rossa White (House Price, Q1 2007)

- Geoff Tucker (Rental, Q4 2006)

- Damien Kiberd (House Price, Q4 2006)

- Pat McArdle (House Price, Q3 2006)

- Marc Coleman (House Price, Q2 2006)

- David Duffy (House Price, Q1 2006)

- Austin Hughes (House Price, Q4 2005)

- David McWilliams (House Price, Q2 2005)

17th Nov 2015

Ronan Lyons, Daft's in-house economist, commenting on the latest Daft research on the Irish property market.

Economists are well known for talking in terms of supply and demand. But supply and demand are really only half the story – those of you who have taken a course in economics will probably remember that every supply and demand curve that meet produce a price and a quantity. Too often, we – economists, policymakers and the public – can get distracted by prices and forget to look at quantities.

This is, I think, crucial to understanding what is happening in the rental market in Ireland currently. There have been calls for controls on rents, or at least on rent increases, and they are well-intentioned: there are a number of households that cannot afford higher rents and thus they are at risk of becoming homeless in the coming months. Restricting the capacity for their rent to increase might help these households.

Unfortunately, it does nothing to address those already homeless or indeed to address the underlying problem in the market, which is not a prices problem, rather it is a quantities one. There are simply not enough properties in the rental market to meet the demand Irish households have. As many international commentators have asked, a natural response is: what happened to all those empty properties?

One issue is that we tended to think of our empty properties as a ghost estates problem. But of the 180,000 units identified in ghost estates, more than half had never even been started – they were just planning permissions on a page – while of the remainder, more than half were occupied. There were roughly 35,000 empty ghost estate units, and almost none in the urban centres.

A second, and related question often asked is: what about NAMA? While NAMA is incredibly opaque, it is relatively clear that the vast bulk of homes it controls which are fit for habitation are occupied. Think of it from their point of view: the best way to get a good price on a block of apartments is to show it can generate solid rental income.

The answer to Ireland's housing shortage is not, therefore, looking to the past. It is about understanding the present and planning for the future. Currently, Ireland has a rapidly growing population by the standards of other developed countries. But very few new homes are being built, either for rent or to buy. In a country that needs at least 25,000 new homes – and realistically more like 40,000, allowing for obsolescence and declining family size – we have struggled to build more than 10,000 the last few years.

At this point, it is often said that Ireland lacks developers and lacks finance for development. While this may be true, a healthy market would attract developers and finance from abroad. And indeed many developers have looked at the Irish market, spotted the strong need for new homes and done some further investigation. But almost all of the foreign interest has ended up deciding against building, because the hard costs of construction are too high relative to people's incomes, and thus relative to sustainable rents.

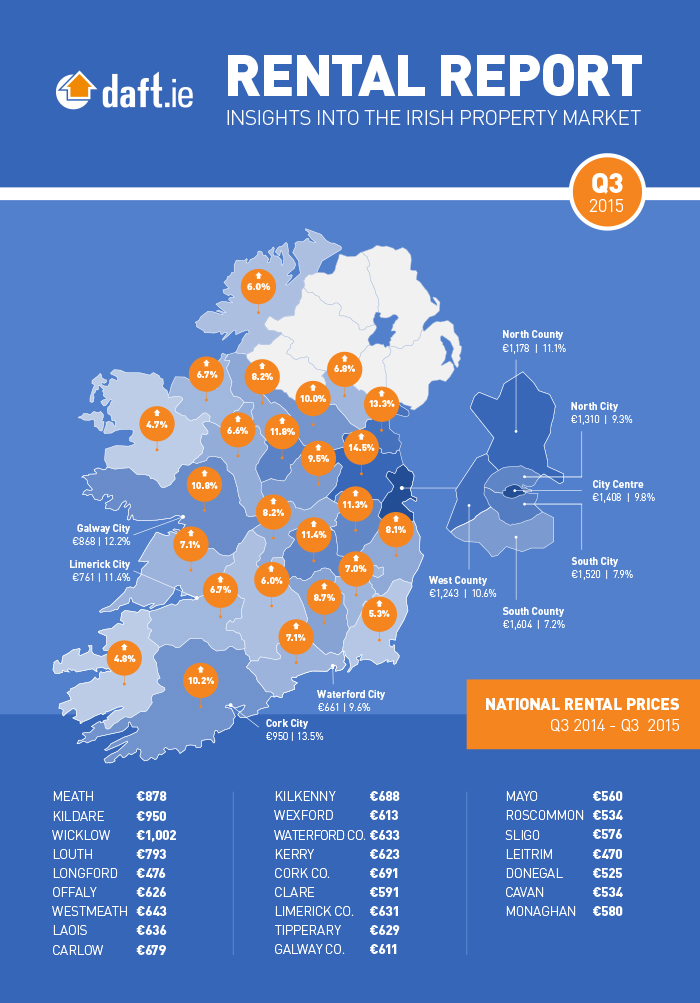

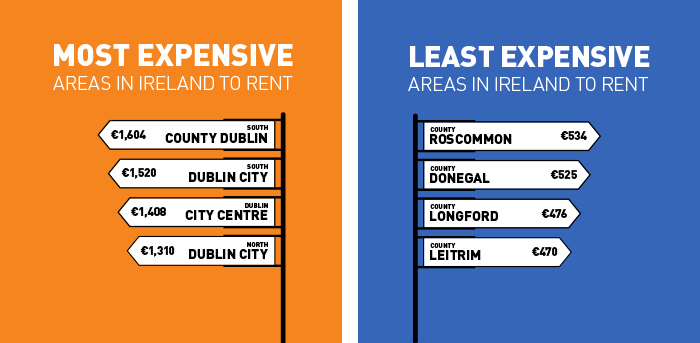

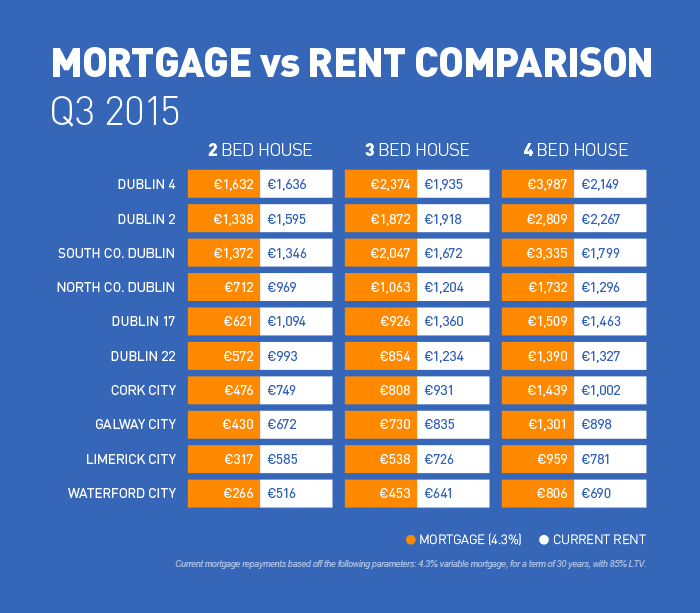

For example, the best figures we have available suggest that to build a two-bedroom apartment and cover costs, excluding land, a rent of roughly €1,400 a month is needed to break even. However, there are very few markets in the country – three out of the 54 analysed in this report, to be precise, and all in central Dublin – where average rents for two-bedroom apartments are at or above €1,400 a month. The cost of construction would need to be roughly half what it is currently in order for it to be viable for either profit or social developers to consider building new homes at scale.

All of this adds up to a large and growing problem. Every year where not enough is being built is another year where all sorts of costly emergency measures are needed in order to give people access to housing, something that should be a human right. Currently, as this latest report shows, there are just 4,000 homes on the rental market, the lowest numbers since figures began back in 2006. But that is 4,000 homes to cater for a renting population that is at least 50% bigger than ten years ago – and probably closer to double the size; we'll find out after the next Census in 2016 – and at a time when nothing is being built.

Capping rent increases is understandable. But it falls into the trap of thinking that prices are the problem and thus price controls are the solution. Prices are a signal and they have been signalling very strong demand for nearly four years now in Dublin – and for nearly two years elsewhere. If we are not seeing new supply being built, then we need to understand why costs are so high, rather than banning rent increases and hoping the problem goes away. While it may not be glamorous and it will certainly not be an overnight solution, the first step to tackling the lack of supply is a Government-sponsored benchmark of construction costs.