Irish Rental Report Q4 2021 | Daft.ie

Daft Reports

- Ronan Lyons (House Price, Q1 2024)

- Ronan Lyons (Rental Price, Q4 2023)

- Ronan Lyons (House Price, Q4 2023)

- Ronan Lyons (Rental Price, Q3 2023)

- Ronan Lyons (House Price, Q3 2023)

- Ronan Lyons (Rental Price, Q2 2023)

- Ronan Lyons (House Price, Q2 2023)

- Ronan Lyons (Rental Price, Q1 2023)

- Ronan Lyons (House Price, Q1 2023)

- Ronan Lyons (Rental Price, Q4 2022)

- Ronan Lyons (House Price, Q4 2022)

- Ronan Lyons (Rental Price, Q3 2022)

- Ronan Lyons (House Price, Q3 2022)

- Ronan Lyons (Rental Price, Q2 2022)

- Ronan Lyons (House Price, Q2 2022)

- Ronan Lyons (Rental Price, Q1 2022)

- Ronan Lyons (House Price, Q1 2022)

- Ronan Lyons (Rental, Q4 2021)

- Ronan Lyons (House Price, Q4 2021)

- Ronan Lyons (Rental, Q3 2021)

- Ronan Lyons (House Price, Q3 2021)

- Ronan Lyons (Rental, Q2 2021)

- Ronan Lyons (House Price, Q2 2021)

- Ronan Lyons (Rental, Q1 2021)

- Ronan Lyons (House Price, Q1 2021)

- Ronan Lyons (Rental, Q4 2020)

- Ronan Lyons (House Price, Q4 2020)

- Ronan Lyons (Wealth, H2 2020)

- Ronan Lyons (Rental, Q3 2020)

- Ronan Lyons (House Price, Q3 2020)

- Ronan Lyons (Housing, July 2020)

- Ronan Lyons (Housing, June 2020)

- Ronan Lyons (Housing, May 2020)

- Ronan Lyons (Rental, Q1 2020)

- Ronan Lyons (House Price, Q1 2020)

- Ronan Lyons (Rental, Q4 2019)

- Ronan Lyons (House Price, Q4 2019)

- Ronan Lyons (Wealth, H2 2019)

- Ronan Lyons (Rental, Q3 2019)

- Ronan Lyons (House Price, Q3 2019)

- Pierre Yimbog (Rental, Q2 2019)

- Ronan Lyons (House Price, Q2 2019)

- Ronan Lyons (Wealth, H1 2019)

- Ronan Lyons (Rental, Q1 2019)

- Ronan Lyons (House Price, Q1 2019)

- Ronan Lyons (Rental, Q4 2018)

- Ronan Lyons (House Price, Q4 2018)

- Ronan Lyons (Wealth, H2 2018)

- Ronan Lyons (Rental, Q3 2018)

- Ronan Lyons (House Price, Q3 2018)

- Shane De Rís (Rental, Q2 2018)

- Ronan Lyons (House Price, Q2 2018)

- Ronan Lyons (Wealth, 2018)

- Ronan Lyons (Rental, Q1 2018)

- Ronan Lyons (House Price, Q1 2018)

- Ronan Lyons (Rental, Q4 2017)

- Ronan Lyons (House Price, Q4 2017)

- Ronan Lyons (Rental, Q3 2017)

- Ronan Lyons (House Price, Q3 2017)

- Katie Ascough (Rental, Q2 2017)

- Ronan Lyons (Wealth, 2017)

- Ronan Lyons (House Price, Q2 2017)

- Ronan Lyons (Rental, Q1 2017)

- Ronan Lyons (House Price, Q1 2017)

- Ronan Lyons (Rental, Q4 2016)

- Ronan Lyons (House Price, Q4 2016)

- Ronan Lyons (Rental, Q3 2016)

- Ronan Lyons (House Price, Q3 2016)

- Ronan Lyons (School Report, 2016)

- Conor Viscardi (Rental, Q2 2016)

- Ronan Lyons (Rail Report, 2016)

- Ronan Lyons (House Price, Q2 2016)

- Ronan Lyons (Rental, Q1 2016)

- Ronan Lyons (House Price, Q1 2016)

- Ronan Lyons (Rental, Q4 2015)

- Ronan Lyons (House Price, Q4 2015)

- Ronan Lyons (Rental, Q3 2015)

- Ronan Lyons (House Price, Q3 2015)

- Marcus O'Halloran (Rental, Q2 2015)

- Ronan Lyons (House Price, Q2 2015)

- Ronan Lyons (Rental, Q1 2015)

- Ronan Lyons (House Price, Q1 2015)

- Ronan Lyons (Rental, Q4 2014)

- Ronan Lyons (House Price, Q4 2014)

- Ronan Lyons (Rental, Q3 2014)

- Ronan Lyons (House Price, Q3 2014)

- Domhnall McGlacken-Byrne (Rental, Q2 2014)

- Ronan Lyons (House Price, Q2 2014)

- Ronan Lyons (Rental, Q1 2014)

- Ronan Lyons (House Price, Q1 2014)

- Ronan Lyons (Rental, Q4 2013)

- Ronan Lyons (House Price, Q4 2013)

- Ronan Lyons (Rental, Q3 2013)

- Ronan Lyons (House Price, Q3 2013)

- Ronan Lyons (Rental, Q2 2013)

- Ronan Lyons (House Price, Q2 2013)

- Ronan Lyons (Rental, Q1 2013)

- Ronan Lyons (House Price, Q1 2013)

- Ronan Lyons (Rental, Q4 2012)

- Ronan Lyons (House Price, Q4 2012)

- Lorcan Sirr (Rental, Q3 2012)

- Padraic Kenna (House Price, Q3 2012)

- John Logue (Rental, Q2 2012)

- Ronan Lyons (House Price, Q2 2012)

- Barry O'Leary (Rental, Q1 2012)

- Seamus Coffey (House Price, Q1 2012)

- Joan Burton (Rental, Q4 2011)

- Ronan Lyons (House Price, Q4 2011)

- Philip O'Sullivan (Rental, Q3 2011)

- Sheila O'Flanagan (House Price, Q3 2011)

- Rachel Breslin (Rental, Q2 2011)

- Constantin Gurdgiev (House Price, Q2 2011)

- Cormac Lucey (Rental, Q1 2011)

- Eoin Fahy (House Price, Q1 2011)

- Lorcan Roche Kelly (Rental, Q4 2010)

- Ronan Lyons (House Price, Q4 2010)

- John Fitzgerald (Rental, Q3 2010)

- Patrick Koucheravy (House Price, Q3 2010)

- Gary Redmond (Rental, Q2 2010)

- Jim Power (House Price, Q2 2010)

- Jill Kerby (Rental, Q1 2010)

- Brian Lucey (House Price, Q1 2010)

- Michael Taft (Rental, Q4 2009)

- Alan McQuaid (House Price, Q4 2009)

- Dr. Charles J. Larkin (Rental, Q3 2009)

- Emer O'Siochru (House Price, Q3 2009)

- Ronan Lyons (Rental, Q2 2009)

- Oliver Gilvarry (House Price, Q2 2009)

- Brian Devine (Rental, Q1 2009)

- Dr. Liam Delaney (House Price, Q1 2009)

- Gerard O'Neill (Rental, Q4 2008)

- Ronan Lyons (House Price, Q4 2008)

- Dr. Stephen Kinsella (Rental, Q3 2008)

- Moore McDowell (House Price, Q3 2008)

- Shane Kelly (Rental, Q2 2008)

- Fergal O'Brien (House Price, Q2 2008)

- Eoin O'Sullivan (Rental, Q1 2008)

- Dermot O'Leary (House Price, Q1 2008)

- Dan O'Brien (Rental, Q4 2007)

- Frances Ruane (House Price, Q4 2007)

- John McCartney (Rental, Q3 2007)

- Ronnie O'Toole (House Price, Q3 2007)

- Ronan Lyons (Rental, Q2 2007)

- Constantin Gurdgiev (House Price, Q2 2007)

- Fintan McNamara (Rental, Q1 2007)

- Rossa White (House Price, Q1 2007)

- Geoff Tucker (Rental, Q4 2006)

- Damien Kiberd (House Price, Q4 2006)

- Pat McArdle (House Price, Q3 2006)

- Marc Coleman (House Price, Q2 2006)

- David Duffy (House Price, Q1 2006)

- Austin Hughes (House Price, Q4 2005)

- David McWilliams (House Price, Q2 2005)

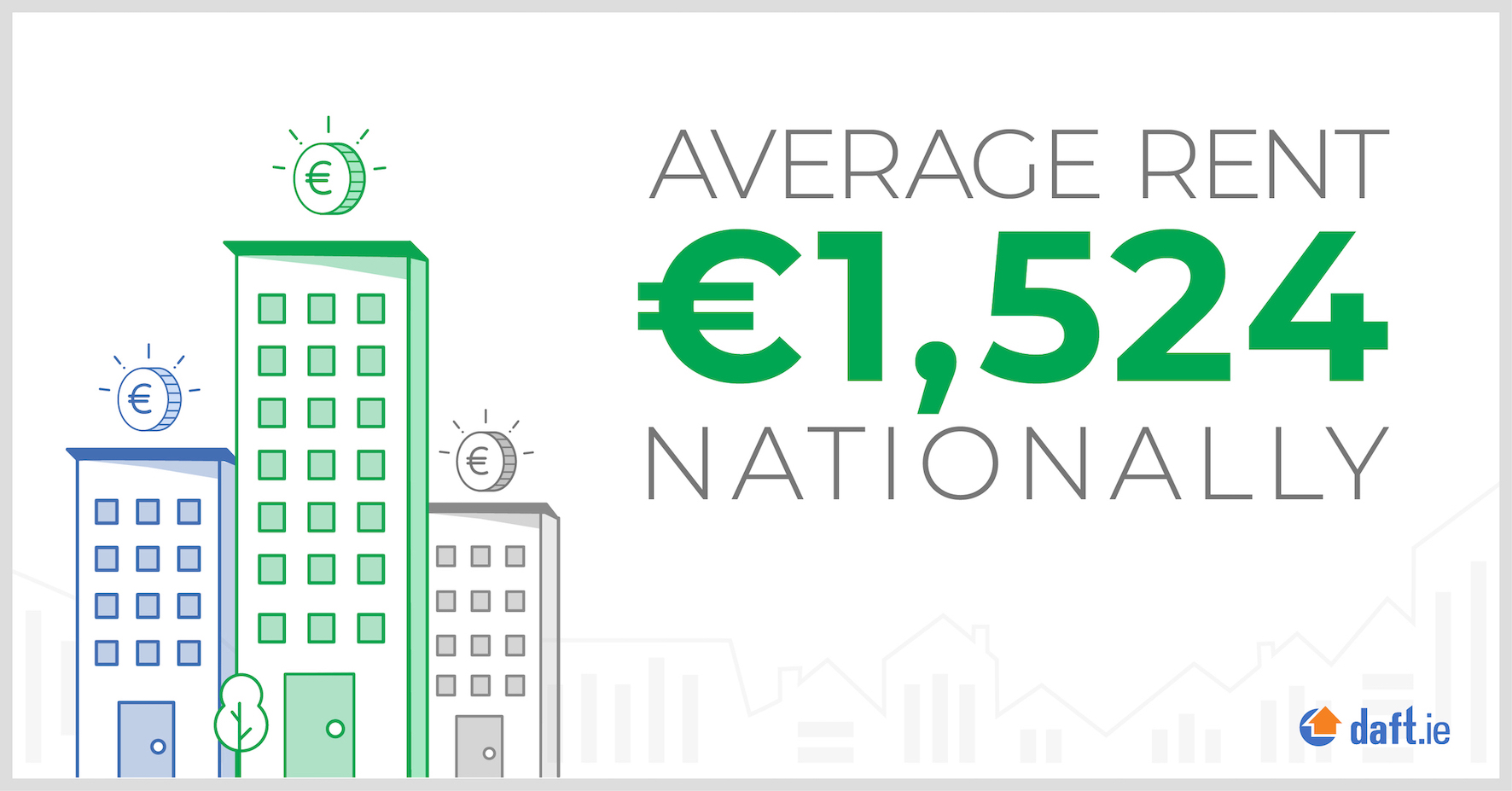

As Ireland's economy recovers, this strength in demand can be seen ‐ unfortunately for those looking to rent ‐ in the figures in this latest Daft.ie Rental Report. Nationally, the rate of inflation for listed rents, a barometer of the open market, stood at over 10% in the final quarter of 2021, its highest rate since early 2018.

The quarterly increase in rents was 3%, similar to the increase seen in the third quarter of the year, but unlike then, it is Dublin now that is bearing the brunt of the pressure. Rents in the capital rose by 4.1% between September and December, the largest three-month increase since early 2014 and a clear signal that ‐ whatever the covid19 lockdowns may have done to the rental market in the capital ‐ demand has clearly returned.

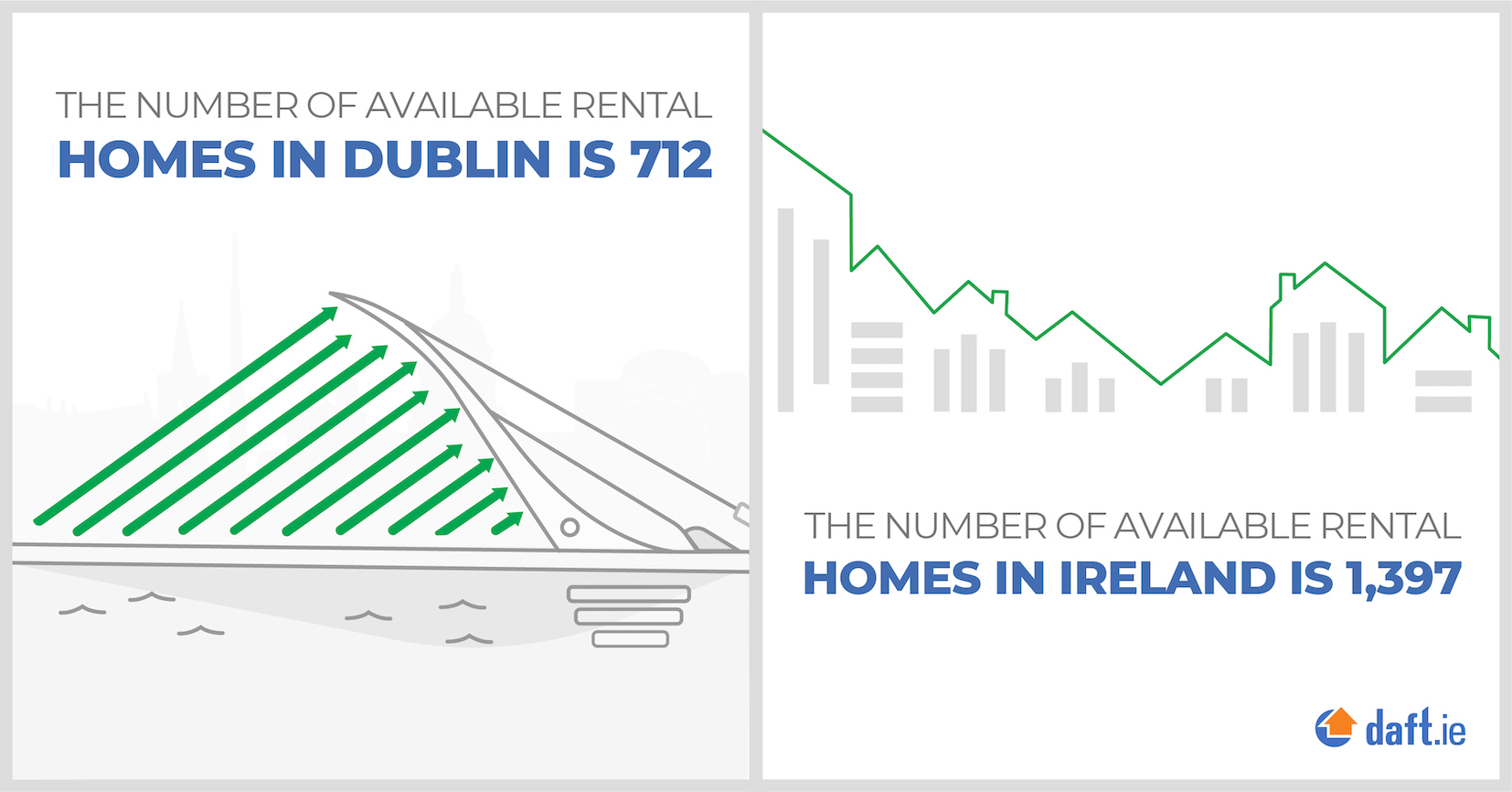

Keen readers of the Daft.ie Reports may be entirely unsurprised by these latest trends. The last edition of the Rental Report, in November, highlighted that the availability of rental homes both nationally and in Dublin was at an all-time low, in a national series stretching back to 2006 ‐ and a Dublin series that goes back to 2002. Over the past two decades, and in line with basic economic theory, tight availability is a harbinger of rising rents and thus if supply was tight in the final few months of 2021, one would expect rents to increase. Unfortunately, the figures for February 1 suggest that, if anything, availability has worsened further since late 2021, with just 712 ads for rental homes in Dublin (down from 820 in November) and 685 in the rest of the country (up slightly from the all-time low of 640).

But is supply really that tight? A narrative has emerged that, while supply might be tight in the traditional rental market dominated by Section 23 and accidental landlords and pre-63s, new private rental sector (PRS) supply changes that picture. For example, Capital Docks has become somewhat infamous in certain circles as an example of new high-spec apartments allegedly left empty while Dublin's renters suffer. However, an examination of publicly available information reveals that it was three quarters full at the start of 2022, with active leases on 142 of its 190 addresses. Two other large high profile rental developments ‐ in Dublin 8 and in Cork city ‐ have occupancy rates of over 80%.

Some might say while four out of every five units being occupied is certainly better than none, if replicated across the city and country ‐ and continued into the future ‐ this would result in thousands of homes being left empty, at a time when Ireland desperately needs new rental homes. But figures from many other PRS developments show far tighter vacancy rates. For example, two medium-sized developments in Glenageary have an estimated 98% occupancy, and similarly there are active leases for almost all of the 442 homes at one development in Dublin 18.

In total, across 63 identifiable PRS complexes completed before 2021, with nearly 7,800 homes, the latest publicly available information suggests that 90% of those ‐ just under 7,000 ‐ are occupied. Compared to the narrative of empty buildings of luxury apartments hulking over the city, the picture from Ireland's PRS sector currently is one of strong demand translating into homes being used. While it does not mean that there is an easy win, for example by forcing professional landlords to rent out homes they are leaving empty, these figures do augur well for Dublin in particular, as it welcomes thousands of new rental homes on to the market: these are not homes that will be left empty, they are homes that will be used.

The Daft Rental Report will continue to monitor occupancy rates in the PRS in subsequent rental reports ‐ adding in new developments as they come on stream. This will allow an understanding of how quickly new PRS stock is absorbed. For example, of twelve developments completed in recent months, with over 2,250 homes, over 500 of those homes were occupied by early January. One new PRS development in Drumcondra, with 342 homes, was highlighted after the last rental report as an example of how simple ad counts could lead the analyst astray when assessing the availability of rental homes. But a closer look confirms the trends seen in the wider market. While there were no active leases in early January for that development, by early February there were already 29. The same is true for other new PRS developments in Clongriffin and Rathgar. These examples of brand new rental homes suggest little reluctance on the part of landlords or tenants to bring these homes into use.

At a rate of one per day, some might argue that it would take all year for the Drumcondra development to be fully occupied. This is, however, largely a function of policy. Ireland's rental controls are designed for a rental sector with 'mom and pop' landlords, owning one or two units each. It is for that reason that rent controls extend, nominally at least, across tenancies. However, within the professional rental sector, the threat of your landlord evicting you “so their niece can go to college" does not exist: the property's owner wants you there as long as you'll stay.

The figures show that it is certainly not a question of whether Ireland's new rental homes will be occupied, but rather how fast. And if unhappy with the pace, it is entirely within the control of government to speed this up. A rent control system that applies within tenancies, rather than across them, would make landlords less fearful of cutting rents in the face of weak demand. There is a clear win-win for policymakers, too, as such a system could be linked to an offer of indefinite tenancies, rather than the current cycle of six-year leases, reducing the uncertainty for landlords while bringing stability of tenure and rents to Ireland's renters.