Irish House Price Report Q4 2017 | Daft.ie

Daft Reports

- Ronan Lyons (House Price, Q1 2024)

- Ronan Lyons (Rental Price, Q4 2023)

- Ronan Lyons (House Price, Q4 2023)

- Ronan Lyons (Rental Price, Q3 2023)

- Ronan Lyons (House Price, Q3 2023)

- Ronan Lyons (Rental Price, Q2 2023)

- Ronan Lyons (House Price, Q2 2023)

- Ronan Lyons (Rental Price, Q1 2023)

- Ronan Lyons (House Price, Q1 2023)

- Ronan Lyons (Rental Price, Q4 2022)

- Ronan Lyons (House Price, Q4 2022)

- Ronan Lyons (Rental Price, Q3 2022)

- Ronan Lyons (House Price, Q3 2022)

- Ronan Lyons (Rental Price, Q2 2022)

- Ronan Lyons (House Price, Q2 2022)

- Ronan Lyons (Rental Price, Q1 2022)

- Ronan Lyons (House Price, Q1 2022)

- Ronan Lyons (Rental, Q4 2021)

- Ronan Lyons (House Price, Q4 2021)

- Ronan Lyons (Rental, Q3 2021)

- Ronan Lyons (House Price, Q3 2021)

- Ronan Lyons (Rental, Q2 2021)

- Ronan Lyons (House Price, Q2 2021)

- Ronan Lyons (Rental, Q1 2021)

- Ronan Lyons (House Price, Q1 2021)

- Ronan Lyons (Rental, Q4 2020)

- Ronan Lyons (House Price, Q4 2020)

- Ronan Lyons (Wealth, H2 2020)

- Ronan Lyons (Rental, Q3 2020)

- Ronan Lyons (House Price, Q3 2020)

- Ronan Lyons (Housing, July 2020)

- Ronan Lyons (Housing, June 2020)

- Ronan Lyons (Housing, May 2020)

- Ronan Lyons (Rental, Q1 2020)

- Ronan Lyons (House Price, Q1 2020)

- Ronan Lyons (Rental, Q4 2019)

- Ronan Lyons (House Price, Q4 2019)

- Ronan Lyons (Wealth, H2 2019)

- Ronan Lyons (Rental, Q3 2019)

- Ronan Lyons (House Price, Q3 2019)

- Pierre Yimbog (Rental, Q2 2019)

- Ronan Lyons (House Price, Q2 2019)

- Ronan Lyons (Wealth, H1 2019)

- Ronan Lyons (Rental, Q1 2019)

- Ronan Lyons (House Price, Q1 2019)

- Ronan Lyons (Rental, Q4 2018)

- Ronan Lyons (House Price, Q4 2018)

- Ronan Lyons (Wealth, H2 2018)

- Ronan Lyons (Rental, Q3 2018)

- Ronan Lyons (House Price, Q3 2018)

- Shane De Rís (Rental, Q2 2018)

- Ronan Lyons (House Price, Q2 2018)

- Ronan Lyons (Wealth, 2018)

- Ronan Lyons (Rental, Q1 2018)

- Ronan Lyons (House Price, Q1 2018)

- Ronan Lyons (Rental, Q4 2017)

- Ronan Lyons (House Price, Q4 2017)

- Ronan Lyons (Rental, Q3 2017)

- Ronan Lyons (House Price, Q3 2017)

- Katie Ascough (Rental, Q2 2017)

- Ronan Lyons (Wealth, 2017)

- Ronan Lyons (House Price, Q2 2017)

- Ronan Lyons (Rental, Q1 2017)

- Ronan Lyons (House Price, Q1 2017)

- Ronan Lyons (Rental, Q4 2016)

- Ronan Lyons (House Price, Q4 2016)

- Ronan Lyons (Rental, Q3 2016)

- Ronan Lyons (House Price, Q3 2016)

- Ronan Lyons (School Report, 2016)

- Conor Viscardi (Rental, Q2 2016)

- Ronan Lyons (Rail Report, 2016)

- Ronan Lyons (House Price, Q2 2016)

- Ronan Lyons (Rental, Q1 2016)

- Ronan Lyons (House Price, Q1 2016)

- Ronan Lyons (Rental, Q4 2015)

- Ronan Lyons (House Price, Q4 2015)

- Ronan Lyons (Rental, Q3 2015)

- Ronan Lyons (House Price, Q3 2015)

- Marcus O'Halloran (Rental, Q2 2015)

- Ronan Lyons (House Price, Q2 2015)

- Ronan Lyons (Rental, Q1 2015)

- Ronan Lyons (House Price, Q1 2015)

- Ronan Lyons (Rental, Q4 2014)

- Ronan Lyons (House Price, Q4 2014)

- Ronan Lyons (Rental, Q3 2014)

- Ronan Lyons (House Price, Q3 2014)

- Domhnall McGlacken-Byrne (Rental, Q2 2014)

- Ronan Lyons (House Price, Q2 2014)

- Ronan Lyons (Rental, Q1 2014)

- Ronan Lyons (House Price, Q1 2014)

- Ronan Lyons (Rental, Q4 2013)

- Ronan Lyons (House Price, Q4 2013)

- Ronan Lyons (Rental, Q3 2013)

- Ronan Lyons (House Price, Q3 2013)

- Ronan Lyons (Rental, Q2 2013)

- Ronan Lyons (House Price, Q2 2013)

- Ronan Lyons (Rental, Q1 2013)

- Ronan Lyons (House Price, Q1 2013)

- Ronan Lyons (Rental, Q4 2012)

- Ronan Lyons (House Price, Q4 2012)

- Lorcan Sirr (Rental, Q3 2012)

- Padraic Kenna (House Price, Q3 2012)

- John Logue (Rental, Q2 2012)

- Ronan Lyons (House Price, Q2 2012)

- Barry O'Leary (Rental, Q1 2012)

- Seamus Coffey (House Price, Q1 2012)

- Joan Burton (Rental, Q4 2011)

- Ronan Lyons (House Price, Q4 2011)

- Philip O'Sullivan (Rental, Q3 2011)

- Sheila O'Flanagan (House Price, Q3 2011)

- Rachel Breslin (Rental, Q2 2011)

- Constantin Gurdgiev (House Price, Q2 2011)

- Cormac Lucey (Rental, Q1 2011)

- Eoin Fahy (House Price, Q1 2011)

- Lorcan Roche Kelly (Rental, Q4 2010)

- Ronan Lyons (House Price, Q4 2010)

- John Fitzgerald (Rental, Q3 2010)

- Patrick Koucheravy (House Price, Q3 2010)

- Gary Redmond (Rental, Q2 2010)

- Jim Power (House Price, Q2 2010)

- Jill Kerby (Rental, Q1 2010)

- Brian Lucey (House Price, Q1 2010)

- Michael Taft (Rental, Q4 2009)

- Alan McQuaid (House Price, Q4 2009)

- Dr. Charles J. Larkin (Rental, Q3 2009)

- Emer O'Siochru (House Price, Q3 2009)

- Ronan Lyons (Rental, Q2 2009)

- Oliver Gilvarry (House Price, Q2 2009)

- Brian Devine (Rental, Q1 2009)

- Dr. Liam Delaney (House Price, Q1 2009)

- Gerard O'Neill (Rental, Q4 2008)

- Ronan Lyons (House Price, Q4 2008)

- Dr. Stephen Kinsella (Rental, Q3 2008)

- Moore McDowell (House Price, Q3 2008)

- Shane Kelly (Rental, Q2 2008)

- Fergal O'Brien (House Price, Q2 2008)

- Eoin O'Sullivan (Rental, Q1 2008)

- Dermot O'Leary (House Price, Q1 2008)

- Dan O'Brien (Rental, Q4 2007)

- Frances Ruane (House Price, Q4 2007)

- John McCartney (Rental, Q3 2007)

- Ronnie O'Toole (House Price, Q3 2007)

- Ronan Lyons (Rental, Q2 2007)

- Constantin Gurdgiev (House Price, Q2 2007)

- Fintan McNamara (Rental, Q1 2007)

- Rossa White (House Price, Q1 2007)

- Geoff Tucker (Rental, Q4 2006)

- Damien Kiberd (House Price, Q4 2006)

- Pat McArdle (House Price, Q3 2006)

- Marc Coleman (House Price, Q2 2006)

- David Duffy (House Price, Q1 2006)

- Austin Hughes (House Price, Q4 2005)

- David McWilliams (House Price, Q2 2005)

A year of two halves

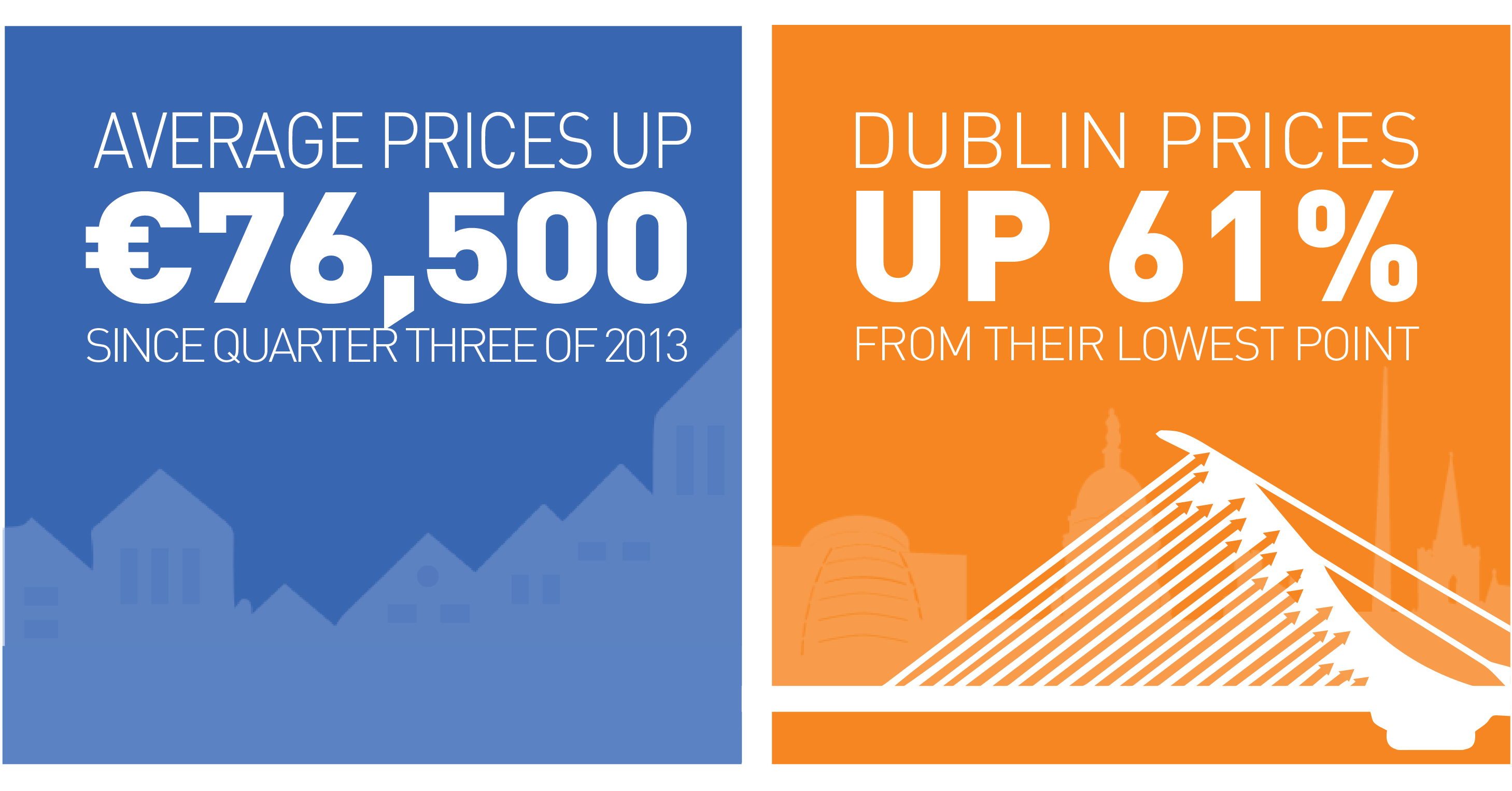

The figures in this year-end Daft.ie Report for the sales segment of the housing market show that 2017 was very much a year of two halves. In the first half of the year, prices rose nationwide by an average of 8.8% - with Dublin (9.5%) and the rest of Leinster (11.4%) seeing the biggest increases regionally.

By contrast, the second six months of the year saw almost no change in the average price: whereas it had been €240,093 in the second quarter, it was €240,783 by the end of the year. Drilling into the regional figures reveals a nuance to this: prices rose by 2% in Dublin from July to December and by 1.5% in the other cities - but fell by 1.3% outside the cities.

How can we interpret these trends? At first pass, this might seem somewhat random. If demand is strong and supply weak, how can it be that two quarters see very strong price gains, while the next two see almost none. But this is to forget the lessons of the bubble and crash.

It is not just fundamentals such as income, demographics and supply that affect the sale price of housing. These are the factors that affect both the sale and rental value of housing. There are also factors that affect the ratio of the two. These 'asset factors' include interest rates, expectations and credit conditions such as the mortgage rules.

When it comes to the sales market, then, the story of 2017 is the story of just how pivotal the Central Bank's mortgage rules are. At the start of the year, the Central Bank relaxed its minimum deposit rules, in particular for wealthier first-time buyers. Whereas previously, any mortgage credit above €220,000 required a 20% deposit, from 2017 all first-time buyers required no more than a 10% deposit, no matter how large their mortgage.

This relaxation of the rules spawned an almost immediate price response in the market. But a one-off change in rules can only bring about a one-off shift in prices. And once this change in credit conditions had been absorbed by the market, the rules kicked in. Incomes are rising but very modestly. Thus the second half of the year was the flip side of the same argument: the Central Bank rules matter when they aren't changed as well as when they are.

Taking a step back, it means that the price at the end of 2017 was 9.2% higher than at the end of 2016. This is a bigger increase than was seen during 2016 (8%) or 2015 (8.5%). Indeed, of the years since 2006, only 2014 - when prices rose 14.2% on average nationwide - saw a bigger increase than the year just gone. (Prices were stable in 2007 and in 2013 and falling for the years in between.)

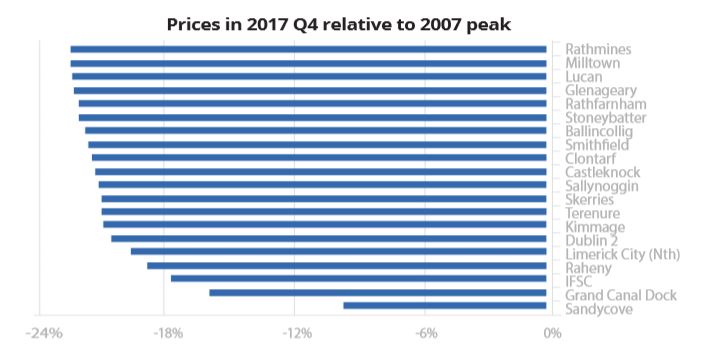

The substantial increases over the last four years mean that in a number of parts of the country, prices are now within a year or two of reaching their 2007 peak. The figure accompanying this commentary shows the 20 areas closest to their Celtic Tiger peak. There are at least two noteworthy points from the graph.

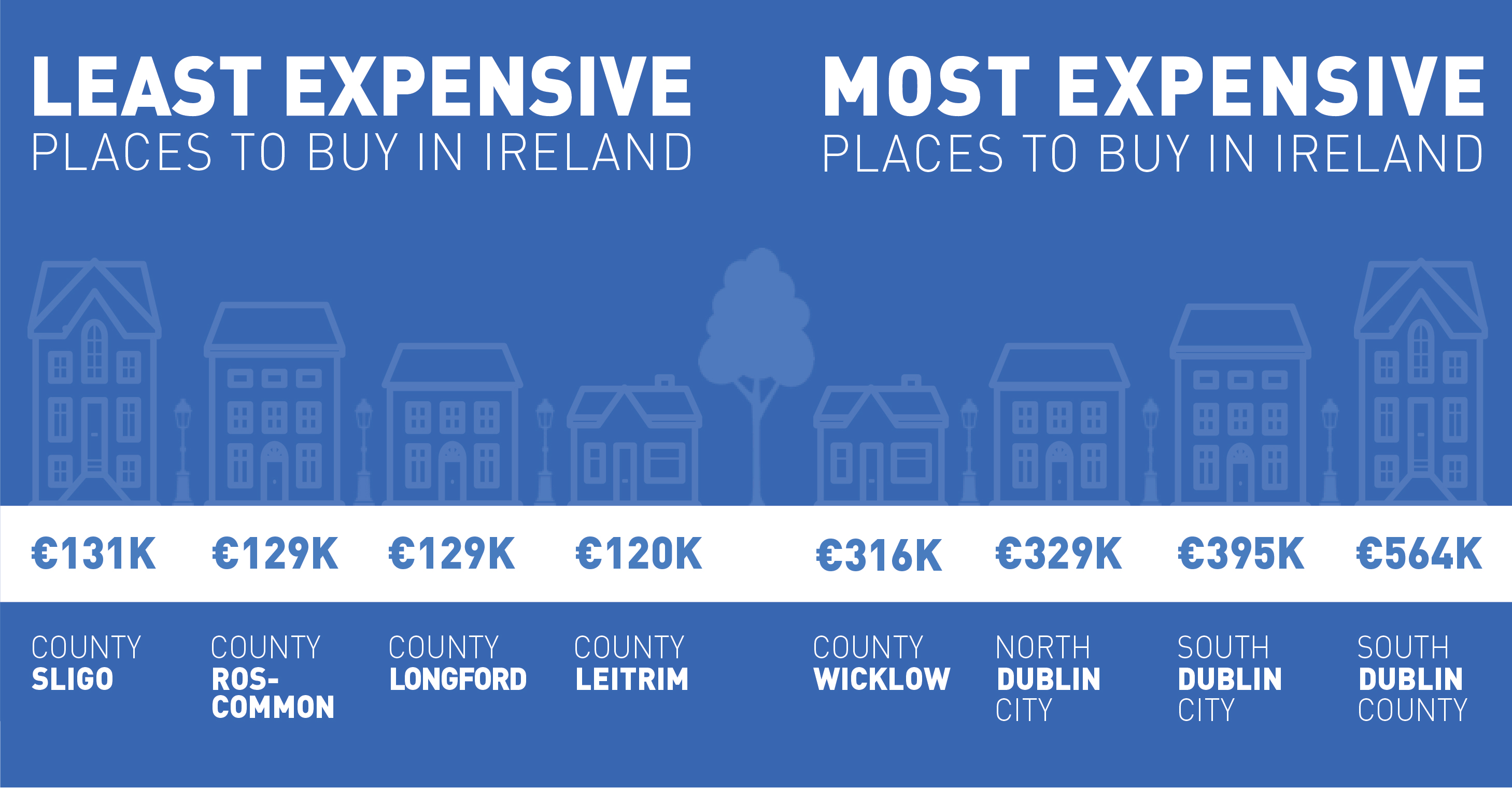

The first is that all the areas closest to their 2007 peak are urban areas. Outside the main cities and the Greater Dublin Area, the typical region has prices that are still 45% below peak values. But in Sandycove, prices are less than 10% below their peak. A natural response to this is that the very top end of the market is a law unto itself and that one cannot read that much into the market as a whole from places like Sandycove or Grand Canal Dock.

However, the second noteworthy point to take from the graph is just how spread out the areas closest to their peak area. It's not only South County Dublin. Areas like Raheny, Stoneybatter, Lucan and Kimmage are as close to their peak as areas like Milltown, Clontarf or Castleknock. And it's not just Dublin too. In North Limerick City, prices are less than 20% from their peak while in Cork City, Ballincollig prices are just 22% off peak.

The peak of the Celtic Tiger housing bubble is not, of course, a target. Apart from those in negative equity, there is little reason to cheer prices as they rise year on year. What the bigger picture price trends tell us is that housing demand is focused in and around cities.

Contrary to some of the political debate in Ireland, this is far from unhealthy. What is unhealthy is trying to impose a non-urbanised housing market on an urbanised labour market. Ireland is the least urbanised country in Europe - but this just makes it late, not different.

As Ireland goes from 65% urban to 80% or 85% over the coming few decades, this will create huge additional demand for housing in and around Ireland's major cities. If we as a country get that wrong, we will be stuck in a sprawl model, with implications for family life and environmental sustainability, as well as for the housing market.

In 2018, work will get underway on implementing the National Planning Framework, which is supposed to put in place the foundations for Ireland to grow over the next two decades. Here's hoping the Framework gets it right. Otherwise, there could be many more years of housing market angst ahead.