Irish Rental Report Q2 2022 | Daft.ie

Daft Reports

- Ronan Lyons (House Price, Q1 2024)

- Ronan Lyons (Rental Price, Q4 2023)

- Ronan Lyons (House Price, Q4 2023)

- Ronan Lyons (Rental Price, Q3 2023)

- Ronan Lyons (House Price, Q3 2023)

- Ronan Lyons (Rental Price, Q2 2023)

- Ronan Lyons (House Price, Q2 2023)

- Ronan Lyons (Rental Price, Q1 2023)

- Ronan Lyons (House Price, Q1 2023)

- Ronan Lyons (Rental Price, Q4 2022)

- Ronan Lyons (House Price, Q4 2022)

- Ronan Lyons (Rental Price, Q3 2022)

- Ronan Lyons (House Price, Q3 2022)

- Ronan Lyons (Rental Price, Q2 2022)

- Ronan Lyons (House Price, Q2 2022)

- Ronan Lyons (Rental Price, Q1 2022)

- Ronan Lyons (House Price, Q1 2022)

- Ronan Lyons (Rental, Q4 2021)

- Ronan Lyons (House Price, Q4 2021)

- Ronan Lyons (Rental, Q3 2021)

- Ronan Lyons (House Price, Q3 2021)

- Ronan Lyons (Rental, Q2 2021)

- Ronan Lyons (House Price, Q2 2021)

- Ronan Lyons (Rental, Q1 2021)

- Ronan Lyons (House Price, Q1 2021)

- Ronan Lyons (Rental, Q4 2020)

- Ronan Lyons (House Price, Q4 2020)

- Ronan Lyons (Wealth, H2 2020)

- Ronan Lyons (Rental, Q3 2020)

- Ronan Lyons (House Price, Q3 2020)

- Ronan Lyons (Housing, July 2020)

- Ronan Lyons (Housing, June 2020)

- Ronan Lyons (Housing, May 2020)

- Ronan Lyons (Rental, Q1 2020)

- Ronan Lyons (House Price, Q1 2020)

- Ronan Lyons (Rental, Q4 2019)

- Ronan Lyons (House Price, Q4 2019)

- Ronan Lyons (Wealth, H2 2019)

- Ronan Lyons (Rental, Q3 2019)

- Ronan Lyons (House Price, Q3 2019)

- Pierre Yimbog (Rental, Q2 2019)

- Ronan Lyons (House Price, Q2 2019)

- Ronan Lyons (Wealth, H1 2019)

- Ronan Lyons (Rental, Q1 2019)

- Ronan Lyons (House Price, Q1 2019)

- Ronan Lyons (Rental, Q4 2018)

- Ronan Lyons (House Price, Q4 2018)

- Ronan Lyons (Wealth, H2 2018)

- Ronan Lyons (Rental, Q3 2018)

- Ronan Lyons (House Price, Q3 2018)

- Shane De Rís (Rental, Q2 2018)

- Ronan Lyons (House Price, Q2 2018)

- Ronan Lyons (Wealth, 2018)

- Ronan Lyons (Rental, Q1 2018)

- Ronan Lyons (House Price, Q1 2018)

- Ronan Lyons (Rental, Q4 2017)

- Ronan Lyons (House Price, Q4 2017)

- Ronan Lyons (Rental, Q3 2017)

- Ronan Lyons (House Price, Q3 2017)

- Katie Ascough (Rental, Q2 2017)

- Ronan Lyons (Wealth, 2017)

- Ronan Lyons (House Price, Q2 2017)

- Ronan Lyons (Rental, Q1 2017)

- Ronan Lyons (House Price, Q1 2017)

- Ronan Lyons (Rental, Q4 2016)

- Ronan Lyons (House Price, Q4 2016)

- Ronan Lyons (Rental, Q3 2016)

- Ronan Lyons (House Price, Q3 2016)

- Ronan Lyons (School Report, 2016)

- Conor Viscardi (Rental, Q2 2016)

- Ronan Lyons (Rail Report, 2016)

- Ronan Lyons (House Price, Q2 2016)

- Ronan Lyons (Rental, Q1 2016)

- Ronan Lyons (House Price, Q1 2016)

- Ronan Lyons (Rental, Q4 2015)

- Ronan Lyons (House Price, Q4 2015)

- Ronan Lyons (Rental, Q3 2015)

- Ronan Lyons (House Price, Q3 2015)

- Marcus O'Halloran (Rental, Q2 2015)

- Ronan Lyons (House Price, Q2 2015)

- Ronan Lyons (Rental, Q1 2015)

- Ronan Lyons (House Price, Q1 2015)

- Ronan Lyons (Rental, Q4 2014)

- Ronan Lyons (House Price, Q4 2014)

- Ronan Lyons (Rental, Q3 2014)

- Ronan Lyons (House Price, Q3 2014)

- Domhnall McGlacken-Byrne (Rental, Q2 2014)

- Ronan Lyons (House Price, Q2 2014)

- Ronan Lyons (Rental, Q1 2014)

- Ronan Lyons (House Price, Q1 2014)

- Ronan Lyons (Rental, Q4 2013)

- Ronan Lyons (House Price, Q4 2013)

- Ronan Lyons (Rental, Q3 2013)

- Ronan Lyons (House Price, Q3 2013)

- Ronan Lyons (Rental, Q2 2013)

- Ronan Lyons (House Price, Q2 2013)

- Ronan Lyons (Rental, Q1 2013)

- Ronan Lyons (House Price, Q1 2013)

- Ronan Lyons (Rental, Q4 2012)

- Ronan Lyons (House Price, Q4 2012)

- Lorcan Sirr (Rental, Q3 2012)

- Padraic Kenna (House Price, Q3 2012)

- John Logue (Rental, Q2 2012)

- Ronan Lyons (House Price, Q2 2012)

- Barry O'Leary (Rental, Q1 2012)

- Seamus Coffey (House Price, Q1 2012)

- Joan Burton (Rental, Q4 2011)

- Ronan Lyons (House Price, Q4 2011)

- Philip O'Sullivan (Rental, Q3 2011)

- Sheila O'Flanagan (House Price, Q3 2011)

- Rachel Breslin (Rental, Q2 2011)

- Constantin Gurdgiev (House Price, Q2 2011)

- Cormac Lucey (Rental, Q1 2011)

- Eoin Fahy (House Price, Q1 2011)

- Lorcan Roche Kelly (Rental, Q4 2010)

- Ronan Lyons (House Price, Q4 2010)

- John Fitzgerald (Rental, Q3 2010)

- Patrick Koucheravy (House Price, Q3 2010)

- Gary Redmond (Rental, Q2 2010)

- Jim Power (House Price, Q2 2010)

- Jill Kerby (Rental, Q1 2010)

- Brian Lucey (House Price, Q1 2010)

- Michael Taft (Rental, Q4 2009)

- Alan McQuaid (House Price, Q4 2009)

- Dr. Charles J. Larkin (Rental, Q3 2009)

- Emer O'Siochru (House Price, Q3 2009)

- Ronan Lyons (Rental, Q2 2009)

- Oliver Gilvarry (House Price, Q2 2009)

- Brian Devine (Rental, Q1 2009)

- Dr. Liam Delaney (House Price, Q1 2009)

- Gerard O'Neill (Rental, Q4 2008)

- Ronan Lyons (House Price, Q4 2008)

- Dr. Stephen Kinsella (Rental, Q3 2008)

- Moore McDowell (House Price, Q3 2008)

- Shane Kelly (Rental, Q2 2008)

- Fergal O'Brien (House Price, Q2 2008)

- Eoin O'Sullivan (Rental, Q1 2008)

- Dermot O'Leary (House Price, Q1 2008)

- Dan O'Brien (Rental, Q4 2007)

- Frances Ruane (House Price, Q4 2007)

- John McCartney (Rental, Q3 2007)

- Ronnie O'Toole (House Price, Q3 2007)

- Ronan Lyons (Rental, Q2 2007)

- Constantin Gurdgiev (House Price, Q2 2007)

- Fintan McNamara (Rental, Q1 2007)

- Rossa White (House Price, Q1 2007)

- Geoff Tucker (Rental, Q4 2006)

- Damien Kiberd (House Price, Q4 2006)

- Pat McArdle (House Price, Q3 2006)

- Marc Coleman (House Price, Q2 2006)

- David Duffy (House Price, Q1 2006)

- Austin Hughes (House Price, Q4 2005)

- David McWilliams (House Price, Q2 2005)

10th Aug 2022

How bad does the rental supply crisis have to get to change minds?

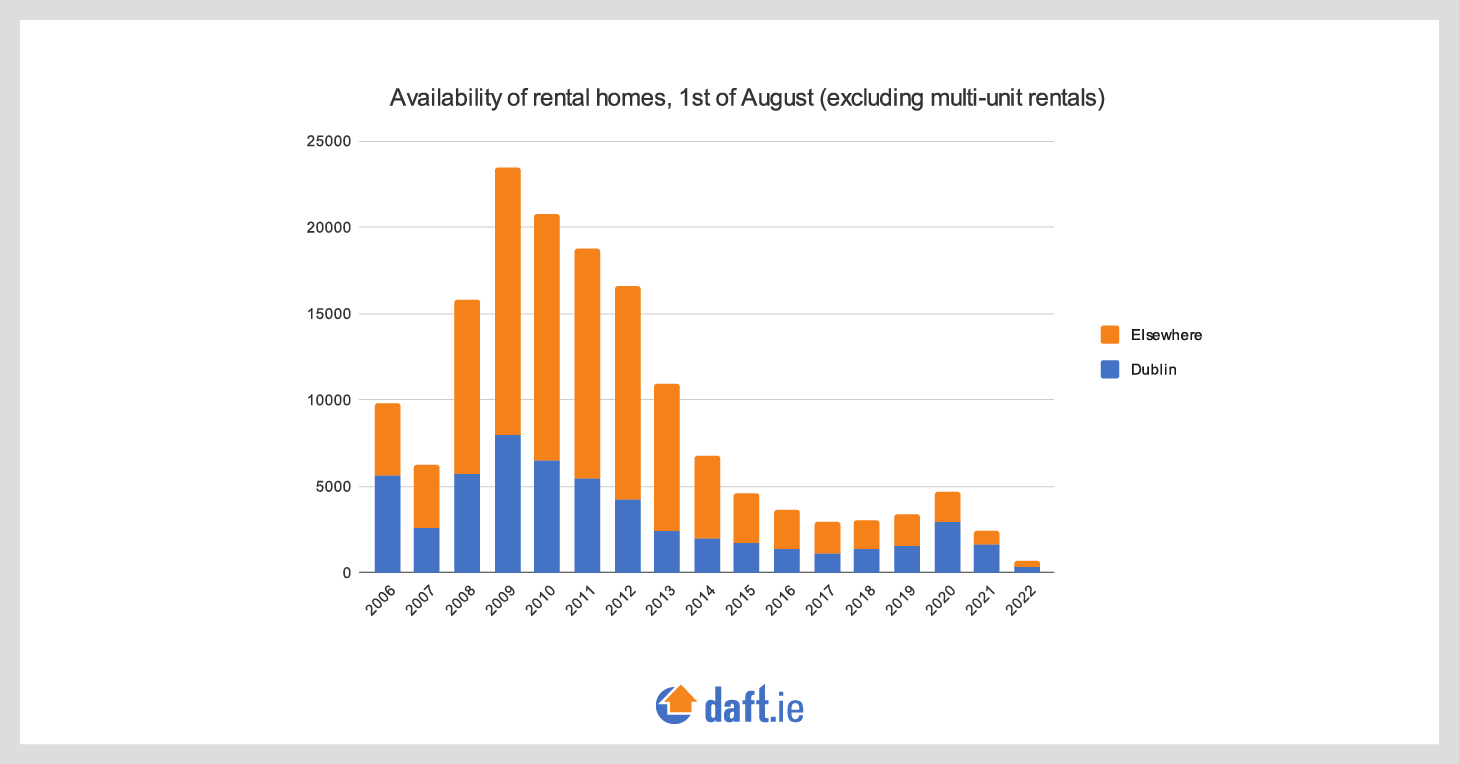

There were fewer than three hundred homes advertised to rent in Dublin on August 1st. To put that number into perspective, we can contrast it with the average number of homes available to rent on the same date in the late 2010s, between 2015 and 2019. During this period of the Celtic Phoenix, there was very tight supply already as the economic recovery gathered pace. But even then, there was an average of just under 1,450 homes available to rent in Dublin at the start of August.

And it's not just a Dublin issue. As shown in the figure accompanying this commentary, the number of homes available to rent elsewhere has also collapsed ‐ and with apologies, the rest of Ireland is grouped into that single category, to keep the story easy to follow... there are no traps in doing so, however, as even splitting the country into sixteen different regional markets would show the same trend everywhere. Outside Dublin, the typical August in the late 2010s saw almost 2,100 homes available to rent at any point in time ‐ although the trend was somewhat downward during those five years ‐ compared to just 424 on August 1st this year.

But, as mentioned above, the rental market was already hungry for more supply in those years. Getting back to the levels of availability in the late 2010s would be merely going to a starving market, from one that is atrophying due to malnutrition, if you'll allow the metaphor to be extended. In August 2009, there were over 23,400 homes available to rent nationwide ‐ nearly 8,000 in Dublin and 15,500 elsewhere. That means that for every 100 homes available to rent thirteen years ago, there are just 3 on the market today.

One could, justifiably, argue that 2009 is the wrong benchmark, as the market had too much supply and too little demand thirteen years ago. That said, it would be impossible for anyone sensible to argue that the 97% reduction in the availability of rental homes is the correct adjustment needed. A halving of supply is more likely to have been sufficient to steady the market.

Perhaps more importantly, whatever about the way things were pre-2015, things since then have been going in only one direction ‐ with the blip of 2020, due to covid19 restrictions only giving way to an extraordinary resumption in the growing scarcity of rental homes over the last 24 months.

However, some might argue that while supply is tight ‐ certainly tighter than during the period 2008-2012 ‐ that things aren't nearly so bad as portrayed by the statistics above. In particular, this argument rests on the idea that multi-unit rentals, i.e. a development owned by one organisation that contains multiple rental homes, will not show up in the individual listings. It is for this reason, indeed, that the title of the graph refers to the exclusion of multi-unit rentals.

The problem with that argument is that while multi-unit rentals, or MURs for short, are a growing feature in the Irish market, firstly they are still very small compared to the overall market size ‐ and in reality negligible outside Dublin ‐ and secondly, their growth is not fast enough to offset the decline in 'traditional' rental supply.

In the 2021 Q4 rental report, we launched a new feature in the rental report, estimating occupancy across a number of MUR developments over time. This measurement exercise started last November and is update monthly, both with figures for existing developments and ‐ where relevant ‐ to include new MUR developments. As detailed in the relevant page of this report, the estimated occupancy across 75 MUR developments stands at 95%, a share that is largely unchanged over the last nine months. (This figure was necessarily a little less precise prior to April, when annual registration of tenancies takes effect.)

While almost 1,000 new tenancies have been added, in net terms, to the 75 MUR developments tracked over the last nine months ‐ one-third of those during July alone ‐ this is small relative to shortfall. One thousand new tenancies in 40 weeks translates into roughly 25 per week. To put this number into context, the Dublin area needs at least 1,000 rental homes per week to 'break even', based on trends over the last decade. This year so far, excluding MURs, it has been getting less than one-third of that.

Including new rental homes that were added over the last year only reduces the estimated shortfall from something like 675 rental homes per week in Dublin to perhaps 650. And it has no effect whatsoever on the shortfall elsewhere in the country, where new MURs have yet to make an appearance. The pipeline of proposed rental homes has grown since this time last year, according to figures provided by Cortland Consult, from 91,250 to 115,000 nationwide ‐ excluding those for which planning was refused. About 22,600 of those are under construction, with a further 43,000 having been granted permission. It is this kind of scale ‐ tens of thousands of homes, not the few thousand that have been added in the last few years ‐ that will be needed to address the chronic shortage of rental homes in the country.

However, so much of the housing policy debate is unfortunately based on the assumption that more professionally run rental housing is, somehow, bad for Ireland. How bad does the rental supply crisis have to get to change people's minds?