Irish Rental Report Q1 2022 | Daft.ie

Daft Reports

- Ronan Lyons (House Price, Q1 2024)

- Ronan Lyons (Rental Price, Q4 2023)

- Ronan Lyons (House Price, Q4 2023)

- Ronan Lyons (Rental Price, Q3 2023)

- Ronan Lyons (House Price, Q3 2023)

- Ronan Lyons (Rental Price, Q2 2023)

- Ronan Lyons (House Price, Q2 2023)

- Ronan Lyons (Rental Price, Q1 2023)

- Ronan Lyons (House Price, Q1 2023)

- Ronan Lyons (Rental Price, Q4 2022)

- Ronan Lyons (House Price, Q4 2022)

- Ronan Lyons (Rental Price, Q3 2022)

- Ronan Lyons (House Price, Q3 2022)

- Ronan Lyons (Rental Price, Q2 2022)

- Ronan Lyons (House Price, Q2 2022)

- Ronan Lyons (Rental Price, Q1 2022)

- Ronan Lyons (House Price, Q1 2022)

- Ronan Lyons (Rental, Q4 2021)

- Ronan Lyons (House Price, Q4 2021)

- Ronan Lyons (Rental, Q3 2021)

- Ronan Lyons (House Price, Q3 2021)

- Ronan Lyons (Rental, Q2 2021)

- Ronan Lyons (House Price, Q2 2021)

- Ronan Lyons (Rental, Q1 2021)

- Ronan Lyons (House Price, Q1 2021)

- Ronan Lyons (Rental, Q4 2020)

- Ronan Lyons (House Price, Q4 2020)

- Ronan Lyons (Wealth, H2 2020)

- Ronan Lyons (Rental, Q3 2020)

- Ronan Lyons (House Price, Q3 2020)

- Ronan Lyons (Housing, July 2020)

- Ronan Lyons (Housing, June 2020)

- Ronan Lyons (Housing, May 2020)

- Ronan Lyons (Rental, Q1 2020)

- Ronan Lyons (House Price, Q1 2020)

- Ronan Lyons (Rental, Q4 2019)

- Ronan Lyons (House Price, Q4 2019)

- Ronan Lyons (Wealth, H2 2019)

- Ronan Lyons (Rental, Q3 2019)

- Ronan Lyons (House Price, Q3 2019)

- Pierre Yimbog (Rental, Q2 2019)

- Ronan Lyons (House Price, Q2 2019)

- Ronan Lyons (Wealth, H1 2019)

- Ronan Lyons (Rental, Q1 2019)

- Ronan Lyons (House Price, Q1 2019)

- Ronan Lyons (Rental, Q4 2018)

- Ronan Lyons (House Price, Q4 2018)

- Ronan Lyons (Wealth, H2 2018)

- Ronan Lyons (Rental, Q3 2018)

- Ronan Lyons (House Price, Q3 2018)

- Shane De Rís (Rental, Q2 2018)

- Ronan Lyons (House Price, Q2 2018)

- Ronan Lyons (Wealth, 2018)

- Ronan Lyons (Rental, Q1 2018)

- Ronan Lyons (House Price, Q1 2018)

- Ronan Lyons (Rental, Q4 2017)

- Ronan Lyons (House Price, Q4 2017)

- Ronan Lyons (Rental, Q3 2017)

- Ronan Lyons (House Price, Q3 2017)

- Katie Ascough (Rental, Q2 2017)

- Ronan Lyons (Wealth, 2017)

- Ronan Lyons (House Price, Q2 2017)

- Ronan Lyons (Rental, Q1 2017)

- Ronan Lyons (House Price, Q1 2017)

- Ronan Lyons (Rental, Q4 2016)

- Ronan Lyons (House Price, Q4 2016)

- Ronan Lyons (Rental, Q3 2016)

- Ronan Lyons (House Price, Q3 2016)

- Ronan Lyons (School Report, 2016)

- Conor Viscardi (Rental, Q2 2016)

- Ronan Lyons (Rail Report, 2016)

- Ronan Lyons (House Price, Q2 2016)

- Ronan Lyons (Rental, Q1 2016)

- Ronan Lyons (House Price, Q1 2016)

- Ronan Lyons (Rental, Q4 2015)

- Ronan Lyons (House Price, Q4 2015)

- Ronan Lyons (Rental, Q3 2015)

- Ronan Lyons (House Price, Q3 2015)

- Marcus O'Halloran (Rental, Q2 2015)

- Ronan Lyons (House Price, Q2 2015)

- Ronan Lyons (Rental, Q1 2015)

- Ronan Lyons (House Price, Q1 2015)

- Ronan Lyons (Rental, Q4 2014)

- Ronan Lyons (House Price, Q4 2014)

- Ronan Lyons (Rental, Q3 2014)

- Ronan Lyons (House Price, Q3 2014)

- Domhnall McGlacken-Byrne (Rental, Q2 2014)

- Ronan Lyons (House Price, Q2 2014)

- Ronan Lyons (Rental, Q1 2014)

- Ronan Lyons (House Price, Q1 2014)

- Ronan Lyons (Rental, Q4 2013)

- Ronan Lyons (House Price, Q4 2013)

- Ronan Lyons (Rental, Q3 2013)

- Ronan Lyons (House Price, Q3 2013)

- Ronan Lyons (Rental, Q2 2013)

- Ronan Lyons (House Price, Q2 2013)

- Ronan Lyons (Rental, Q1 2013)

- Ronan Lyons (House Price, Q1 2013)

- Ronan Lyons (Rental, Q4 2012)

- Ronan Lyons (House Price, Q4 2012)

- Lorcan Sirr (Rental, Q3 2012)

- Padraic Kenna (House Price, Q3 2012)

- John Logue (Rental, Q2 2012)

- Ronan Lyons (House Price, Q2 2012)

- Barry O'Leary (Rental, Q1 2012)

- Seamus Coffey (House Price, Q1 2012)

- Joan Burton (Rental, Q4 2011)

- Ronan Lyons (House Price, Q4 2011)

- Philip O'Sullivan (Rental, Q3 2011)

- Sheila O'Flanagan (House Price, Q3 2011)

- Rachel Breslin (Rental, Q2 2011)

- Constantin Gurdgiev (House Price, Q2 2011)

- Cormac Lucey (Rental, Q1 2011)

- Eoin Fahy (House Price, Q1 2011)

- Lorcan Roche Kelly (Rental, Q4 2010)

- Ronan Lyons (House Price, Q4 2010)

- John Fitzgerald (Rental, Q3 2010)

- Patrick Koucheravy (House Price, Q3 2010)

- Gary Redmond (Rental, Q2 2010)

- Jim Power (House Price, Q2 2010)

- Jill Kerby (Rental, Q1 2010)

- Brian Lucey (House Price, Q1 2010)

- Michael Taft (Rental, Q4 2009)

- Alan McQuaid (House Price, Q4 2009)

- Dr. Charles J. Larkin (Rental, Q3 2009)

- Emer O'Siochru (House Price, Q3 2009)

- Ronan Lyons (Rental, Q2 2009)

- Oliver Gilvarry (House Price, Q2 2009)

- Brian Devine (Rental, Q1 2009)

- Dr. Liam Delaney (House Price, Q1 2009)

- Gerard O'Neill (Rental, Q4 2008)

- Ronan Lyons (House Price, Q4 2008)

- Dr. Stephen Kinsella (Rental, Q3 2008)

- Moore McDowell (House Price, Q3 2008)

- Shane Kelly (Rental, Q2 2008)

- Fergal O'Brien (House Price, Q2 2008)

- Eoin O'Sullivan (Rental, Q1 2008)

- Dermot O'Leary (House Price, Q1 2008)

- Dan O'Brien (Rental, Q4 2007)

- Frances Ruane (House Price, Q4 2007)

- John McCartney (Rental, Q3 2007)

- Ronnie O'Toole (House Price, Q3 2007)

- Ronan Lyons (Rental, Q2 2007)

- Constantin Gurdgiev (House Price, Q2 2007)

- Fintan McNamara (Rental, Q1 2007)

- Rossa White (House Price, Q1 2007)

- Geoff Tucker (Rental, Q4 2006)

- Damien Kiberd (House Price, Q4 2006)

- Pat McArdle (House Price, Q3 2006)

- Marc Coleman (House Price, Q2 2006)

- David Duffy (House Price, Q1 2006)

- Austin Hughes (House Price, Q4 2005)

- David McWilliams (House Price, Q2 2005)

12th May 2022

With supply so weak, a two-tier rental market has emerged

In some ways, for Ireland's rental sector, it's like the pandemic never happened. As covid19 moves from a shock that brought daily life to a standstill, to something more like part of daily life, pre-existing patterns and pressures are re-emerging in the rental market. The figures in this latest Daft.ie Rental Report confirm, for example, that for prospective tenants of new leases ‐ 'movers' ‐ things have, as best we can tell, never been so grim.

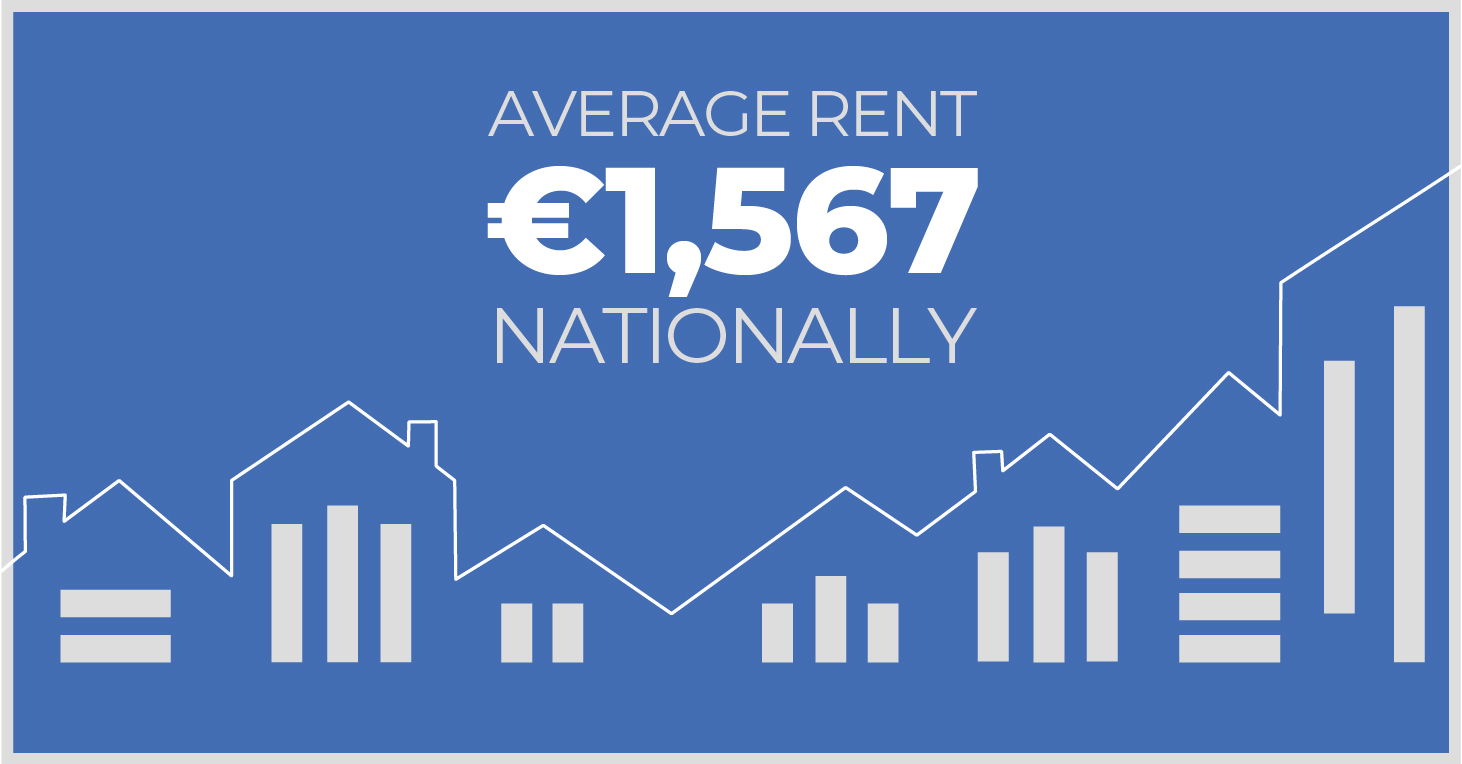

One of the most obvious ways to come to that conclusion is to look at the level and change in listed market rents, i.e. what someone would pay if they were to move into a newly rented home currently. The average market rent, per month, rose just over €1,400 a year ago to €1,567 in the first quarter of 2022. This level of rents is over twice the low of €765 per month, seen just over a decade ago in late 2011. It is also more than 50% higher than the Celtic Tiger peak of €1,030 per month, seen in the first quarter of 2008.

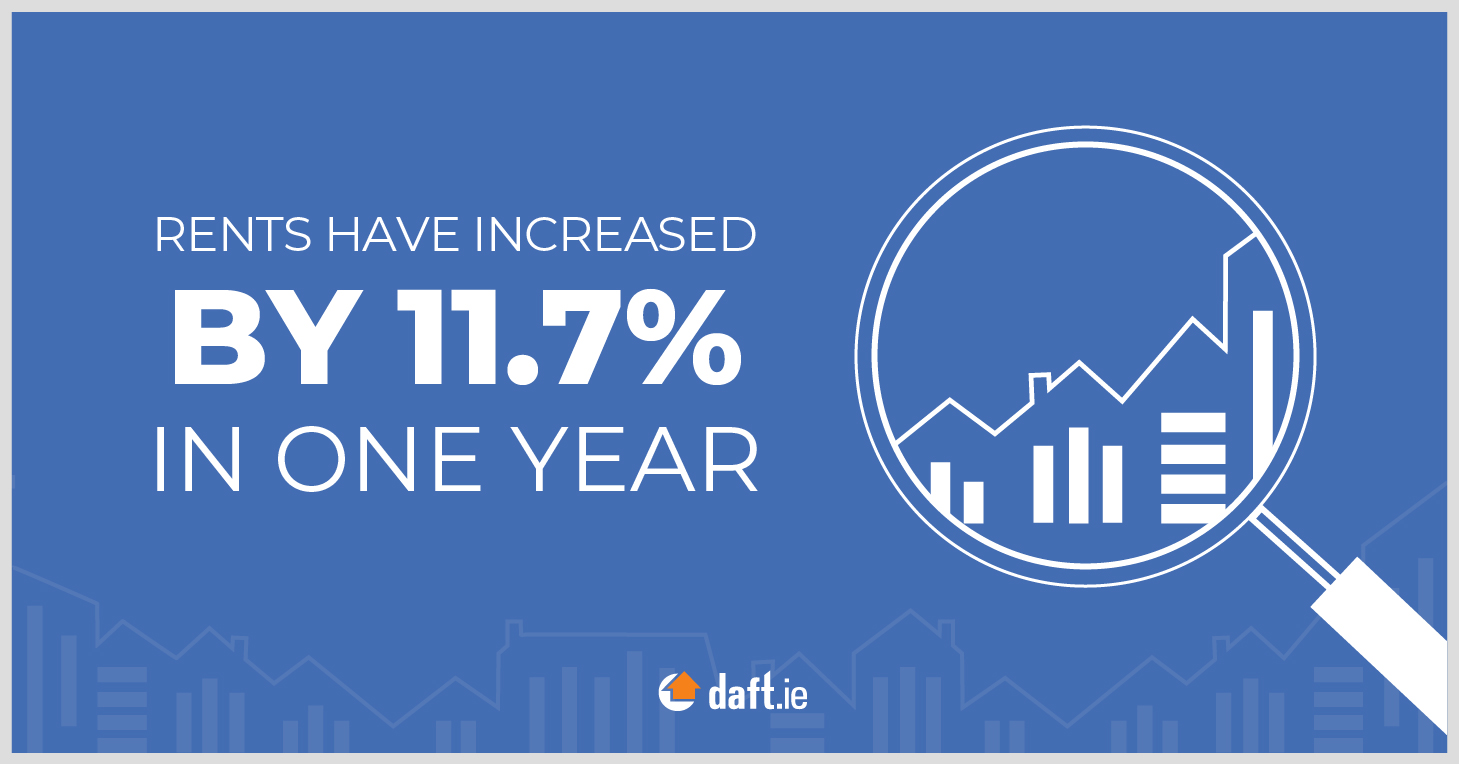

Perhaps more worryingly, it is not only market rental levels that are increasing but also the inflation rate in market rents, which hit 11.7% in the first quarter of 2022, up from just 1.2% a year earlier and only just below the all-time high of 11.8% experienced in late 2016. The surge in inflation had been driven by rural areas, which recovered first from the initial shock of covid19. But in recent months, urban rents have increased strongly. Inflation in market rents for Dublin 2, for example, now stands at almost 11% year-on-year, compared to -9% a year ago and just 1% two years ago.

Indeed, this is an important part of understanding what's different now compared to 2019. In 2019, the rental market appeared to be calming down, with inflation in Dublin, for example, falling from 11% in early 2018 to just 1% in early 2020. The pattern elsewhere in the country was similar, driven by a stabilization and then modest recovery in the availability of homes to rent.

In Dublin, for example, there were almost 1,750 homes available to rent on 1 January 2020, up nearly 30% from the 1,350 available two years earlier. Outside Dublin, the number available had also increased ‐ from 1,900 to 2,200. This meant that, on the cusp of covid19 in early 2020, there were roughly 4,000 homes on the market at any one point in time.

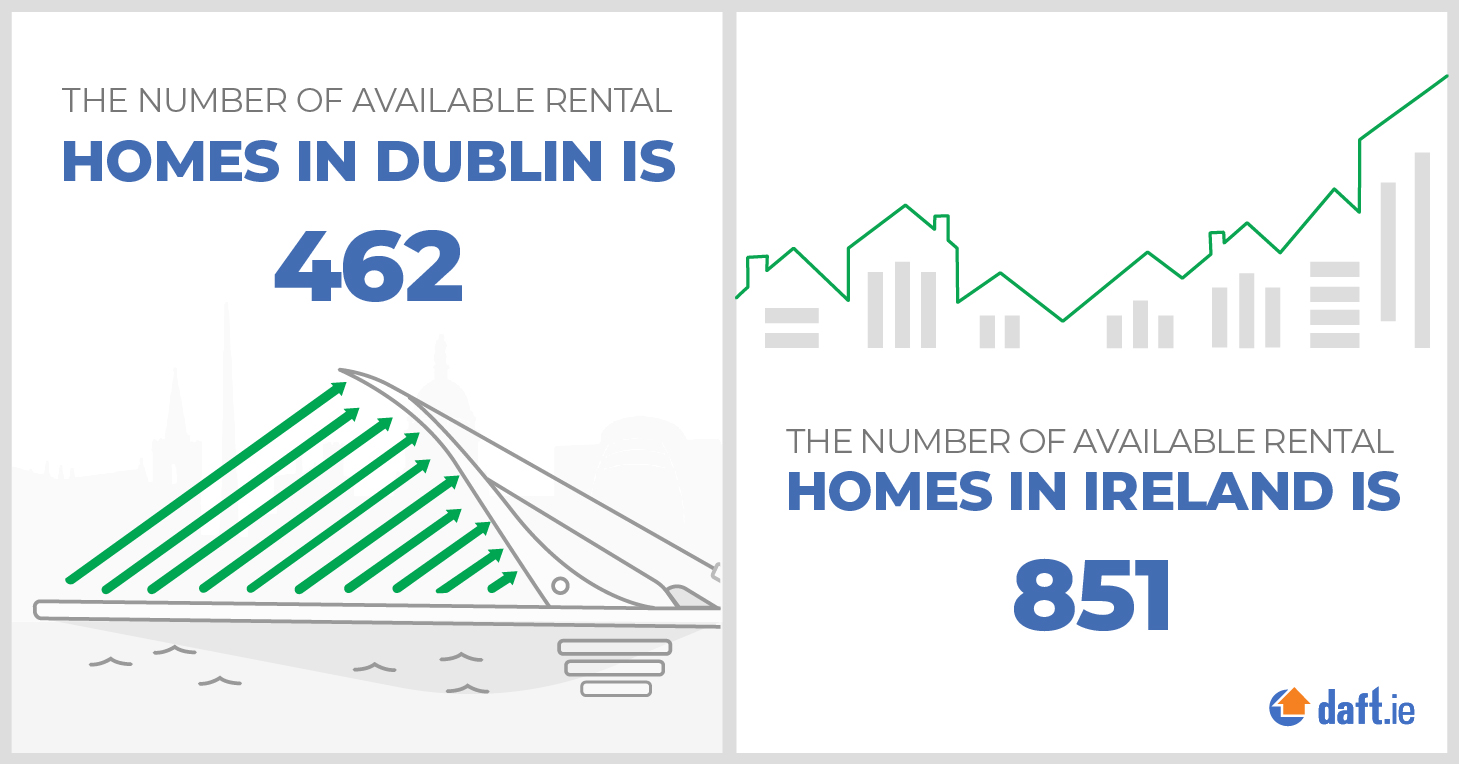

Availability of new rental homes has collapsed since then. On May 1st this year, there were just 851 homes available to rent nationwide ‐ down 77% year-on-year and a frankly unprecedented number in a series extending back to the start of 2006. The average number of homes available to rent nationwide at any point in time over the fifteen-year period 2006-2021 was nearly 9,200 ‐ over ten times the supply available currently.

Such figures are based on ads on daft.ie and, of course, may underestimate the number of homes truly available if newly-built multi-unit rental developments ‐ whether Build-to-Rent (BTR) specifically or Private Rental Sector (PRS) more generally ‐ are opening up. Over the last six months, we have set up a system for measuring occupancy in these multi-unit rentals (MURs) and have identified 72 different developments for which reliable information on take-up is available. Of these, 14 are new-to-market, while the remaining 58 have been active for a year or more.

Between the start of November and early May, we estimate that, in these developments alone, the MUR sector added 400 units to Ireland's rental capacity, bringing the total number of homes in the developments analysed from a little less than 6,900 to nearly 7,300. Further, we estimate that the occupancy of these developments is almost 96%. This breaks down into a 96.6% estimated occupancy for the original 58 developments ‐ an increase of 2 percentage points from the level of occupancy seen six months ago ‐ and an occupancy rate of 82% for the portions of the 14 new MUR developments that have opened within the last year.

With tens of thousands more homes in MUR developments due to come on to the market over the next few years, and with lots of commentary on whether PRS and BTR are appropriate for the Irish market, we will continue to undertake and improve this analysis. But even if they are only "ball-park accurate", they suggest that there is not enough in the MUR developments ‐ perhaps only a few hundred homes ‐ to overturn the extraordinary tightening in rental supply in the 'traditional' rental market described above. And even then, any MUR capacity is in the Dublin area only. The tightening of supply seen elsewhere is just as stark: there were just 64 homes to rent in Cork, Galway, Limerick and Waterford cities combined on May 1st, compared to over 350 during 2019 ‐ an already low figure.

What of the average tenant, then? Also added in this rental report is a new measure of the rents paid by sitting tenants. The rent levels and changes given in the Daft.ie Rental Reports over nearly two decades have focused on market rents ‐ as is standard. However, the introduction of Rent Pressure Zones, linked as they are with increasingly scarce supply, has driven a wedge between what might be termed 'mover' rents and 'stayer' rents.

Over the past five years, Daft.ie has surveyed sitting tenants and, by asking them their path of rents from the start of their lease, has built up a picture of 'stayer' rents to complement the more standard measure of market or 'mover' rents. Focusing on stayers, rather than movers, gives a very different picture not of the direction of rents but of the speed at which they have risen in recent years.

While market rents have risen by 38% since the start of 2017 ‐ and more than doubled in a decade ‐ rents for those who have stayed put are, on average, just 10% higher now than in early 2017 and about 40% higher than a decade ago. In Dublin, the gap in rent increases since 2017 between movers (28%) and stayers (15%) is smaller than in the rest of the country (50% vs. 6%). But nonetheless, these substantial gaps across all markets raise awkward questions about the focus over the last few years by policymakers on protecting rents for sitting tenants.

As ever, in a rental market dogged by chronic and worsening shortage of homes, the only real solution is to increase the number of homes. With more pressure from certain quarters to stop new rental homes being built, policymakers must hold their nerve.